Quick Facts

Biography

Masanobu Fukuoka (福岡 正信) (2 February 1913 – 16 August 2008) was a Japanese farmer and philosopher celebrated for his natural farming and re-vegetation of desertified lands. He was a proponent of no-till, no-herbicide grain cultivation farming methods traditional to many indigenous cultures, from which he created a particular method of farming, commonly referred to as "Natural Farming" or "Do-nothing Farming".

Fukuoka was the author of several Japanese books, scientific papers and other publications, and was featured in television documentaries and interviews from the 1970s onwards. His influences went beyond farming to inspire individuals within the natural food and lifestyle movements. He was an outspoken advocate of the value of observing nature's principles.

Life

Fukuoka was born on 2 February 1913 in Iyo, Ehime, Japan, the second son of Kameichi Fukuoka, an educated and wealthy land owner and local leader. He attended Gifu Prefecture Agricultural College and trained as a microbiologist and agricultural scientist, beginning a career as a research scientist specialising in plant pathology. He worked at the Plant Inspection Division of the Yokohama Customs Bureau in 1934 as an agricultural customs inspector. In 1937 he was hospitalised with pneumonia, and while recovering, he stated that, he had a profound spiritual experience that transformed his world view and led him to doubt the practices of modern "Western" agricultural science. He immediately resigned from his post as a research scientist, returning to his family's farm on the island of Shikoku in southern Japan.

From 1938, Fukuoka began to practise and experiment with new techniques on organic citrus orchards and used the observations gained to develop the idea of "Natural Farming". Among other practices, he abandoned pruning an area of citrus trees, which caused the trees to become affected by insects and tangled branches. He stated that the experience taught him the difference between nature and non-intervention. His efforts were interrupted by World War II, during which he worked at the Kōchi Prefecture agricultural experiment station on subjects including farming research and food production.

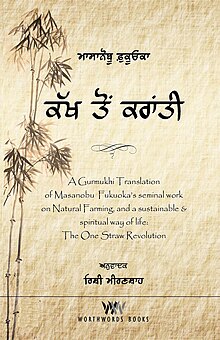

In 1940, Fukuoka married his wife Ayako, and they had five children together. After World War II, his father lost most of the family lands due to forced redistribution policies of the American occupying forces and was left with only three-eighths of an acre of rice land and the hillside citrus orchards his son had taken over before the war. Despite these setbacks, in 1947 he took up natural farming again with success, using no-till farming methods to raise rice and barley. He wrote his first book Mu 1: The God Revolution, or Mu 1: Kami no Kakumei (無〈1〉神の革命) in Japanese, during the same year, and worked to spread word of the benefits of his methods and philosophy. His later book, The One-Straw Revolution was published in 1975 and translated into English in 1978.

From 1979, Fukuoka travelled the world extensively, giving lectures, working directly to plant seeds and re-vegetate areas, and receiving a number of awards in various countries in recognition of his work and achievements. By the 1980s, Fukuoka recorded that he and his family shipped some 6,000 crates of citrus to Tokyo each year totalling about 90 tonnes.

During his first journey overseas, Fukuoka was accompanied by his wife Ayako, met macrobiotic diet leaders Michio Kushi and Herman Aihara, and was guided by his leading supporter and translation editor Larry Korn. They sowed seeds in desertified land, visited the University of California in Berkeley and Los Angeles, the Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, the Lundberg Family Farms, and met with United Nations UNCCD representatives including Maurice Strong, who encouraged Fukuoka's practical involvement in the "Plan of Action to Combat Desertification". He also travelled to New York City and surrounding areas such as Boston and Amherst College in Massachusetts.

In 1983, he travelled to Europe for 50 days holding workshops, educating farmers and sowing seeds. In 1985, he spent 40 days in Somalia and Ethiopia, sowing seeds to re-vegetate desert areas, including working in remote villages and a refugee camp. The following year he returned to the United States, speaking at three international conferences on natural farming in Washington state, San Francisco and at the Agriculture Department of the University of California, Santa Cruz. Fukuoka also took the opportunity to visit farms, forests and cities giving lectures and meeting people. In 1988, he lectured at the Indian Science Congress, state agricultural universities and other venues.

Fukuoka went to Thailand in 1990 and 1991, visiting farms and collecting seeds for re-vegetating deserts in India, which he returned to during November and December that year in an attempt to re-vegetate them. The next year saw him participate in official meetings in Japan associated with the Earth Summit in Rio, Brazil, and in 1996 he returned to Africa, sowing seeds in desert areas of Tanzania, observing Baobab trees and jungle country. He taught the making and sowing of clay seed balls in Vietnam during 1995.

He travelled to the Philippines in 1998, carrying out Natural Farming research, and visited Greece later that year to assist plans to re-vegetate 10,000 hectares around the Lake Vegoritis area in the Pella regional unit and to produce a film of the major seed ball effort. The next year he returned to Europe, visiting Mallorca.

He visited China in 2001, and in 2002 he returned again to India to speak at the "Nature as Teacher" workshop at Navdanya Farm and at Bija Vidyapeeth Earth University in Dehra Dun, Uttarakhand in northern India. On Gandhi's Day, he gave the third annual Albert Howard Memorial Lecture to attendees from all six continents. That autumn he was to visit Afghanistan with Yuko Honma but was unable to attend, shipping eight tons of seed in his stead. In 2005, he gave a brief lecture at the World Expo in Aichi Prefecture, Japan, and in May 2006 he appeared in an hour-long interview on Japanese television network NHK.

Masanobu Fukuoka died on 16 August 2008 at the age of 95, after a period of confinement in bed and in a wheelchair.

Natural Farming

Fukuoka called his agricultural philosophy shizen nōhō (自然農法), most commonly translated into English as "natural farming". It is also referred to as "the Fukuoka Method", "the natural way of farming" or "Do-Nothing Farming".

The system is based on the recognition of the complexity of living organisms that shape an ecosystem and deliberately exploiting it. Fukuoka saw farming not just as a means of producing food but as an aesthetic and spiritual approach to life, the ultimate goal of which was "the cultivation and perfection of human beings".

The five principles of Natural Farming are that:

- human cultivation of soil, plowing or tilling are unnecessary, as is the use of powered machines

- prepared fertilizers are unnecessary, as is the process of preparing compost

- weeding, either by cultivation or by herbicides, is unnecessary. Instead only minimal weed suppression with minimal disturbance

- applications of pesticides or herbicides are unnecessary

- pruning of fruit trees is unnecessary

- 1975 (Japanese) 自然農法-わら一本の革命 (English) 1978 translation and reinterpretation The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming

- Linking foresight and sustainability: An integral approach Joshua Floyd, Kipling Zubevich Strategic Foresight Program and National Centre for Sustainability, Swinburne University of Technology

- Agriculture: A Fundamental Principle, Hanley Paul. Journal of Bahá’í Studies Vol. 3, number 1, 1990.

- From the ground up: rethinking industrial agriculture By Helena Norberg-Hodge, Peter Goering, John Page, International Society for Ecology and Culture

- Sustainable Agriculture: A Vision for Future by Desai, B.K. and B.T.Pujari. New India Publishing, 2007

Clay seed balls

Fukuoka re-invented and advanced the use of clay seed balls. Clay seeds balls were originally an ancient practice in which seeds for the next season's crops are mixed together, sometimes with humus or compost for microbial inoculants, and then are rolled within clay to form into small balls. This method is now commonly used in guerilla gardening to rapidly seed restricted or private areas.

Awards

In 1988, Fukuoka received Visva-Bharati University's Desikottam Award as well as the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service in the Philippines, often considered "Asia's Nobel Prize".

In March 1997, the Earth Summit+5 forum in Rio de Janeiro presented him with the Earth Council Award, received in person at a ceremony in Tokyo on 26 May of that year, honouring him for his contributions to sustainable development.

In 1998, Fukuoka received a grant of US$10,000 from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund but the grant was returned because his advanced age prevented him from completing the project.

Influence

In the international development of the organic farming movement, Fukuoka is considered to be amongst the "five giant personalities who inspired the movement" along with Austrian Rudolf Steiner, German-Swiss Hans Müller, Lady Eve Balfour in the United Kingdom and J.I. Rodale in the United States.

His books are considered both farming compendiums and guides to a way of life.:(1)

The One-Straw Revolution has been translated into over 20 languages and sold more than one million copies and Fukuoka has been widely influential, inspiring an international movement of individuals discovering and applying his principles to varying degrees, such as Akinori Kimura, David Mas Masumoto and Yoshikazu Kawaguchi, and has significantly influenced alternative movements in the West, such as permaculture.

Rosana Tositrakul, a Thai activist and politician, spent a year studying with Fukuoka on his farm. She then organised a visit by Fukuoka to the Kut Chum District of northern Thailand, which, together with his books, were influential in the rapid and widespread adoption of organic and chemical-free rice farming in the district.

Criticism

In the preface to the US editions of The One-Straw Revolution, Wendell Berry wrote that the Natural Farming system would not be directly applicable to most American farms. Fukuoka's techniques have proven difficult to apply, even on most Japanese farms, and are seen as too technically demanding for most people to follow. It has been described as a sophisticated approach despite its simple appearance. In the initial years of transition from conventional farming there are losses in crop yields. Fukuoka estimated these to be 10% while others, such as Yoshikazu Kawaguchi, have found attempting to strictly follow Fukuoka's techniques lead to crop failures and require many years of adaption to make the principles work.

Theodor Friedrich and Josef Kienzle of the Food and Agriculture Organization opined that his rejection of mechanisation is not justifiable for modern agricultural productionand that the system cannot interact effectively with conventional agricultural systems.

In Japan, where Fukuoka had few followers or associates, his critics argue that the "inner world and the connection between humans and nature does not, however, exhaust reality" and that he did not give sufficient attention to interpersonal relationships or society.

Family farm recent developments

Fukuoka's farm in Shikoku was taken over by his son and daughter-in-law in the late 1980s, as Fukuoka reached an advanced age and his grandson also took up farming. Many of the farm's iyokan and amanatsu mikan trees remain, although some old iyokan were replaced by new varieties of fruit. Woodlands remain along with orchards, including some areas of wild vegetables still growing amongst them. Some areas of straw-mulched cropping continue to produce grains and vegetables. The farm also features an orchard area of ginkgo trees, shiitake mushroom crops growing on tree logs in shady woodland, and plantings of limes, grapefruits, feijoas, avocados and mangos.

The farm is now run using some natural farming techniques: no chemicals, no tillage of the land and no use of composting. Other techniques have been changed the pattern of irrigation is more conventional to reduce conflicts with neighbours. A do nothing philosophy has been followed on the hilltop surrounding Fukuoka's hut. Here it has been to become a natural, fruit-bearing forest with minimal intervention.

Selected works

Articles

- "柑橘樹脂病特にその完全時代に就て" [(A study) On Citrus gummosis (fungus): specifically in its Perfect State (sexually-reproductive state)] (PDF). Annals of the Phytopathological Society of Japan (in Japanese). The Phytopathological Society of Japan. 7 (1): 32–33. August 1937. ISSN 0031-9473. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- "私の農法(講演〔「近代農法の反省と今後の農業」セミナーより)" [My farming ways (A lecture at the "Reflecting on modern-day farming ways and considering the future of farming" seminar)]. Cooperative Research Institute Monthly Report (in Japanese). Cooperative Research Institute (214): 19–36. July 1971. ISSN 0914-1758. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- "智慧とは何か - 仏教の知 現代の知" [What is Wisdom?: Buddhist way-of-knowing Present-day way-of-knowing]. Quarterly Buddhism (in Japanese). 7. Hōzōkan. May 1989: 159–. ISBN 978-4-8318-0207-1. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- "いのちの環境" [Life's environment]. Quarterly Buddhism - Supplementary Issue (in Japanese). 6. Hōzōkan. November 1991: 52–. ISBN 978-4-8318-0256-9. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- "「日本仏教」批判" ["Japanese Buddhism" A Criticism]. Quarterly Buddhism (in Japanese). 25. Hōzōkan. October 1993: 130–. ISBN 978-4-8318-0225-5. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- "森の哲学 - 新たな宗教哲学をめざして" [Forest's Philosophy - Toward a new philosophy of religion]. Quarterly Buddhism (in Japanese). 28. Hōzōkan. July 1994: 176–. ISBN 978-4-8318-0228-6. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

Japanese

- 1947 – 『無』 (mu), self-published, incorporated into later editions.

- 1958 – 『百姓夜話・「付」自然農法』 (hyakushō yawa・「fu」shizen nōhō), self-published, later incorporated into 『無 神の革命』 (mu kami no kakumei).

- 1969 – 『無2 緑の哲学』 (mu 2: midori no tetsugaku), self-published, republished as 『無2 無の哲学』 (mu 2: mu no tetsugaku) Shunjūsha (春秋社?), Tokyo, 1985. ISBN 978-4-393-74112-2.

- 1972 – 『無3 自然農法』 (mu 3: shizen nōhō), self-published; republished by Shunjūsha (春秋社?), 1985, ISBN 978-4-393-74113-9.

- 1973 – 『無1 神の革命』 (mu 1: kami no kakumei), self-published; republished by Shunjūsha (春秋社?), 1985, ISBN 978-4-393-74111-5.

- 1974 – 『無 別冊 緑の哲学 農業革命論』 (mu: bessatsu midori no tetsugaku nōgyō kakumei ron), self-published.

- 1975 – 『自然農法 わら一本の革命』 (shizen nōhō wara ippon no kakumei), republished Shunjūsha (春秋社?), 1983, ISBN 978-4-393-74103-0.

- 1975 – 『自然農法 緑の哲学の理論と実践』 (shizen nōhō midori no tetsugaku no riron to jissen), Jiji Press Co. (時事通信社 jiji tsūshinsha) j, ISBN 978-4-7887-7626-5.13-3.

- 1984 – 『自然に還る』 (shizen ni kaeru), Shunjūsha (春秋社?) j, ISBN 978-4-393-74104-7.

- 1992 – 『「神と自然と人の革命」わら一本の革命・総括編』 (「kami to shizen to hito no kakumei」wara ippon no kakumei・sōkatsuhen), self-published, ISBN 978-4-938743-01-7.

- 1997 – with Toshio Kanamitsu (金光 寿郎) 『「自然」を生きる』 ("shizen" o ikiru), Shunjūsha (春秋社?), ISBN 978-4-393-74115-3.

- 2001 – 『わら一本の革命 総括編 —粘土団子の旅—』 (wara ippon no kakumei sōkatsuhen -nendo dango no tabi-), self-published, republished by Shunjūsha (春秋社?). 2010. ISBN 978-4-393-74151-1.

- 2005 – 『自然農法 福岡正信の世界』 (shizen nōhō Fukuoka Masanobu no sekai), Shunjūsha (春秋社?), ISBN 978-4-393-97019-5.

English

- 1978 [1975 Sep.] – The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming, translators Chris Pearce, Tsune Kurosawa and Larry Korn, Rodale Press.

- 1985 [1975 Dec.] – The Natural Way Of Farming - The Theory and Practice of Green Philosophy, translator Frederic P. Metreaud, published by Japan Publications, ISBN 978-0-87040-613-3.

- 1987 [1984 Aug.] – The Road Back to Nature - Regaining the Paradise Lost, translator Frederic P. Metreaud, published by Japan Publications, ISBN 978-0-87040-673-7.

- 1996 [1992 Dec.] – The Ultimatum of God Nature The One-Straw Revolution A Recapitulation; English translation, published without ISBN by "Shou Shin Sha (小心舎)".

- 2012 [–1996] – Sowing Seeds in the Desert: Natural Farming, Global Restoration, and Ultimate Food Security, edited by Larry Korn, Chelsea Green.

Bilingual

- 2009 – Iroha Revolutionary Verses (いろは革命歌 Iroha Kakumei Uta), Fukuoka, Masanobu's hand-written classical song-verses and drawings. Bilingual Japanese and English. (ISBN 978-4-938743-03-1, ISBN 4-938743-03-5).

Documentaries

- 1982 – The Close To Nature Garden; produced by Rodale Press. 24 minutes. In English.

- 1997 – Fukuoka Masanobu goes to India; produced by Salbong. 59/61 minutes. Available in Japanese or dubbed English.

- 2015 - Final Straw: Food, Earth, Happiness; directed/produced by Patrick M. Lydon and Suhee Kang. 74 minutes. Subtitled in English.