Quick Facts

Biography

Ala ud-Din Khilji (r. 1296-1316) was the second and the most powerful ruler of the Khilji dynasty of Delhi Sultanate in the Indian subcontinent.

Alauddin was a nephew and a son-in-law of his predecessor Jalaluddin. When Jalaluddin became the Sultan of Delhi after deposing the Mamluks, Alauddin was given the position of Amir-i-Tuzuk (equivalent to Master of ceremonies). Alauddin obtained the governorship of Kara in 1291 after suppressing a revolt against Jalaluddin, and the governorship of Awadh in 1296 after a profitable raid on Bhilsa. In 1296, Alauddin raided Devagiri, and used the loot to stage a successful revolt against Jalaluddin. After killing Jalaluddin, he consolidated his power in Delhi, and subjugated Jalalaudidn's sons in Multan.

Over the next few years, Alauddin successfully defended India against the Mongol invasions, at Jaran-Manjur (1297-1298), Sivistan (1298), Kili (1299), Delhi (1303), and Amroha (1305). In 1306, his forces achieved a decisive victory against the Mongols near the Ravi riverbank, and in the subsequent years, his forces ransacked the Mongol territories in present-day Afghanistan.

Alauddin subjugated the Hindu kingdoms of Gujarat (raided in 1299 and annexed in 1304), Ranthambore (1301), Chittor (1303), Malwa (1305), Siwana (1308), and Jalore (1311). These victories ended several Hindu dynasties, including the Paramaras, the Vaghelas, the Chahamanas of Ranastambhapura and Jalore, the Rawal branch of the Guhilas, and possibly the Yajvapalas. Alauddin's slave-general Malik Kafur led multiple campaigns to the south of the Vindhyas, obtaining a huge amount of wealth from Devagiri (1308), Warangal (1310) and Dwarasamudra (1311). These victories forced the Yadava king Ramachandra, the Kakatiya king Prataparudra, and the Hoysala king Ballala III to become Alauddin's tributaries. Kafur also raided the Pandya kingdom (1311), obtaining a large number of treasures, elephants and horses.

During the last years of his life, Alauddin suffered from an illness, and relied on Malik Kafur to handle the administration. After his death in 1316, Malik Kafur appointed his son Shihabuddin as a puppet monarch, but his elder son Qutbuddin Mubarak Shah seized the power shortly after.

Early life

Contemporary chroniclers did not write much about Alauddin's childhood. According to the 16th-17th century chronicler Haji-ud-Dabir, Alauddin was 34 years old when he started his march to Ranthambore (1300-1301). Assuming this is correct, Alauddin's birth can be dated to 1266-1267. His original name was Ali Gurshasp. He was the eldest son of Shihabuddin Mas'ud, who was the elder brother of the Khilji dynasty's founder Sultan Jalaluddin. He had three brothers: Almas Beg (later Ulugh Khan), Qutlugh Tigin and Muhammad.

Alauddin was brought up by Jalaluddin after Shihabuddin's death. Both Alauddin and his younger brother Almas Beg married Jalaluddin's daughters. After Jalaluddin became the Sultan of Delhi, Alauddin was appointed as Amir-i-Tuzuk (equivalent to Master of ceremonies), while Almas Beg was given the post of Akhur-beg (equivalent to Master of the Horse).

Alauddin's marriage to Jalaluddin's daughter was not a happy one. Having suddenly become a princess after Jalaluddin's rise as a monarch, she was very arrogant and tried to dominate Alauddin. According to Haji-ud-Dabir, Alauddin married a second woman, named Mahru, who was the sister of Malik Sanjar alias Alp Khan. Once, while Alauddin and Mahru were together in a garden, Jalaluddin's daughter attacked Mahru. In response, Alauddin assaulted her. The incident was reported to Jalaluddin, but the Sultan did not take any action against Alauddin. Alauddin was not on good terms with his mother-in-law either. According to the 16th-century historian Firishta, she warned Jalaluddin that Alauddin was planning to set up an independent kingdom in a remote part of the country. She kept a close watch on Alauddin, and encouraged her daughter's arrogant behaviour towards him.

In 1291, Alauddin played an important role in crushing a revolt by the governor of Kara Malik Chajju. As a result, Jalaluddin appointed him as the new governor of Kara in 1291. Malik Chajju's former Amirs (subordinate nobles) at Kara considered Jalaluddin as a weak and ineffective ruler, and instigated Alauddin to usurp the throne of Delhi. This, combined with his unhappy domestic life, made Alauddin determined to dethrone Jalaluddin.

Conspiracy against Jalaluddin

While instigating Alauddin to revolt against Jalaluddin, Malik Chajju's supporters emphasized that he needed a lot of money to raise a large army and stage a successful coup: Malik Chajju's revolt had failed for want of resources. To finance his plan to dethrone Jalaluddin, Alauddin decided to raid the neighbouring Hindu kingdoms. In 1293, he raided Bhilsa, a wealthy town in the Paramara kingdom of Malwa, which had been weakened by multiple invasions. He surrendered the loot to Jalaluddin to win the Sultan's confidence. A pleased Jalaluddin gave him the office of Ariz-i Mamalik (Minister of War), and also made him the governor of Awadh. In addition, the Sultan granted Alauddin's request to use the revenue surplus for hiring additional troops.

During his raid of Bhilsa, Alauddin had learned about the immense wealth of Devagiri, the capital of the southern Yadava kingdom in the Deccan region. After years of planning and preparation, he successfully raided Devagiri in 1296. He left Devagiri with a huge amount of wealth, including precious metals, jewels, silk products, elephants, horses, and slaves. When the news of Alauddin's success reached Jalaluddin, the Sultan came to Gwalior, hoping that Alauddin would present the loot to him there. However, Alauddin marched directly to Kara with all the wealth. Jalaluddin's advisors such as Ahmad Chap recommended intercepting Alauddin at Chanderi, but Jalaluddin had faith in his nephew. He returned to Delhi, believing that Alauddin would carry the wealth from Kara to Delhi. After reaching Kara, Alauddin sent a letter of apology to the Sultan, and expressed concern that his enemies may have poisoned the Sultan's mind against him during his absence. He requested a letter of pardon signed by the Sultan, which the Sultan immediately despatched through messengers. At Kara, Jalaluddin's messengers learned of Alauddin's military strength and of his plans to dethrone the Sultan. However, Alauddin detained them, and prevented them from communicating with the Sultan.

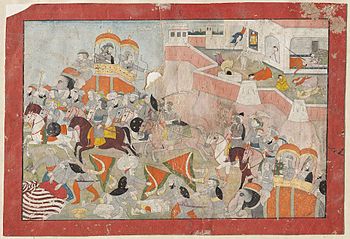

Meanwhile, Alauddin's younger brother Almas Beg (later Ulugh Khan), who was married to a daughter of Jalaluddin, assured the Sultan of Alauddin's loyalty. He convinced Jalaluddin to visit Kara and meet Alauddin, saying that Alauddin would commit suicide out of guilt if the Sultan didn't pardon him personally. A gullible Jalaluddin set out for Kara with his army. After reaching close to Kara, he directed Ahmad Chap to take his main army to Kara by the land route, while he himself decided to cross the Ganges river with a smaller body of around 1,000 soldiers. On 20 July 1296, Alauddin killed Jalaluddin after pretending to greet the Sultan, and declared himself the new king. Jalaluddin's companions were also killed, while Ahmad Chap's army retreated to Delhi.

Ascension and march to Delhi

Alauddin, known as Ali Gurshasp until his ascension in July 1296, was formally proclaimed as the new king with the title Alauddunya wad Din Muhammad Shah-us Sultan at Kara. Meanwhile, the head of Jalaluddin was circulated on a spear in his camp before being sent to Awadh. Over the next two days, Alauddin formed a provisional government at Kara. He promoted the existing Amirs to the rank of Maliks, and appointed his close friends as the new Amirs.

At that time, there were heavy rains, and the Ganga and the Yamuna rivers were flooded. But Alauddin made preparations for a march to Delhi, and ordered his officers to recruit as many soldiers as possible, without fitness tests or background checks. His objective was to cause a change in the general political opinion, by portraying himself as someone with huge public support. To portray himself as a generous king, he ordered 5 manns of gold pieces to be shot from a manjaniq (catapult) at a crowd in Kara.

One section of his army, led by himself and Nusrat Khan, marched to Delhi via Badaun and Baran (modern Bulandshahr). The other section, led by Zafar Khan, marched to Delhi via Koil (modern Aligarh). As Alauddin marched to Delhi, the news spread in towns and villages that he was recruiting soldiers while distributing gold. A large number of people, from both military and non-military backgrounds, joined him. By the time he reached Badaun, he had a 56,000-strong cavalry and a 60,000-strong infantry. At Baran, Alauddin was joined by seven powerful Jalaluddin's nobles who had earlier opposed him. These nobles were Tajul Mulk Kuchi, Malik Abaji Akhur-bek, Malik Amir Ali Diwana, Malik Usman Amir-akhur, Malik Amir Khan, Malik Umar Surkha and Malik Hiranmar. Alauddin gave each of them 30 to 50 manns of gold, and each of their soldiers 300 silver tankas (hammered coins).

Alauddin's march to Delhi was interrupted by the flooding of the Yamuna river. Meanwhile, in Delhi, Jalaluddin's widow Malka-i-Jahan appointed her youngest son Qadr Khan as the new king with title Ruknuddin Ibrahim, without consulting the nobles. This irked Arkali Khan, her elder son and the governor of Multan. When Malika-i-Jahan heard that Jalaluddin's nobles had joined Alauddin, she apologized to Arkali and offered him the throne, requesting him to march from Multan to Delhi. However, Arkali refused to come to her aid.

Alauddin resumed his march to Delhi in the second week of October 1296, when the Yamuna river subsided. When he reached Siri, Ruknuddin led an army against him. However, a section of Ruknuddin's army defected to Alauddin at midnight. A dejected Ruknuddin then retreated and escaped to Multan with his mother and the loyal nobles. Alauddin then entered the city, where a number of nobles and officials accepted his authority. On 21 October 1296, Alauddin was formally proclaimed as the Sultan in Delhi.

Consolidation of power

Initially, Alauddin consolidated power by making generous grants and endowments, and appointing a large number of people in the government offices. He balanced the power between the officers appointed by the Mamlluks, the ones appointed by Jalaluddin and his own appointees. He also increased the strength of the Sultanate's army, and gifted every soldier the salary of a year and a half in cash. Of Alauddin's first year as the Sultan, Ziauddin Barani wrote that it was the happiest year that the people of Delhi had ever seen.

At this time, Alauddin's could not exercise his authority over all of Jalaluddin's former territories. In the Punjab region, his authority was limited to the areas east of the Ravi river. The region beyond Lahore suffered from Mongol raids and Khokhar rebellions. Multan was controlled by Jalaluddin's son Arkali, who harboured the fugitives from Delhi. In November 1296, Alauddin sent an army led by Ulugh Khan and Zafar Khan to conquer Multan. On his orders, Nusrat Khan arrested, blinded and/or killed the surviving members of Jalaluddin's surviving family.

Shortly after the conquest of Multan, Alauddin appointed Nusrat Khan as his wazir (prime minister). Having strengthened his control over Delhi, the Sultan started eliminating the officers that were not his own appointees. The aristocrats (maliks), who had deserted Jalaluddin's family to join Alauddin, were arrested, blinded or killed. All their property, including the money earlier given to them by Alauddin, was confiscated. As a result of these confiscations, Nusrat Khan obtained a huge amount of cash for the royal treasury. Only three maliks from Jalaluddin's time were spared: Malik Qutbuddin Alavi, Malik Nasiruddin Rana, Malik Amir Jamal Khalji. The rest of the older aristocrats were replaced with the new nobles, who were extremely loyal to Alauddin.

Meanwhile, Ala-ul Mulk, who was Alaudidn's governor at Kara, came to Delhi with all the officers, elephants and wealth that Alauddin had left at Kara. Alauddin appointed Ala-ul Mulk as the kotwal of Delhi, and placed all the non-Turkic municipal employees under his charge. Since Ala-ul Mulk had become very obese, the fief of Kara was entrusted to Nusrat Khan, who had become unpopular in Delhi because of the confiscations.

Mongol invasions and northern conquests, 1297-1306

In the winter of 1297, the Mongols led by a noyan of the Chagatai Khanate raided Punjab, advancing as far as Kasur. Alauddin's forces, led by Ulugh Khan, defeated the Mongols on 6 February 1298. According to Amir Khusrow, 20,000 Mongols were killed in the battle, and many more were killed in Delhi after being brought there as prisoners. In 1298-99, another Mongol army (possibly Neguderi fugitives) invaded Sindh, and occupied the fort of Sivistan. This time, Alauddin's general Zafar Khan defeated the invaders, and recaptured the fort.

In early 1299, Alauddin sent Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan to invade Gujarat, where the Vaghela king Karna offered a weak resistance. Alauddin's army plundered several towns including Somnath, where it desecrated the famous Hindu temple. The Delhi army also captured several people, including the Vaghela queen Kamala Devi, and the slave Malik Kafur, who later led Alauddin's southern campaigns. During the army's return journey to Delhi, some of its Mongol soldiers staged an unsuccessful mutiny near Jalore, after the generals forcibly tried to extract a share of loot (khums) from them. Alauddin's administration meted out brutal punishments to the mutineers' families in Delhi, including killings of children in front of their mothers. According to the Delhi chronicler Ziauddin Barani, the practice of punishing wives and children for the crimes of men started with this incident in Delhi.

In 1299, the Chagatai ruler Duwa sent a Mongol force led by Qutlugh Khwaja to conquer Delhi. In the ensuing Battle of Kili, Alauddin personally led the Delhi forces, but his general Zafar Khan attacked the Mongols without waiting for his orders. Although Zafar Khan managed to inflict heavy casualties on the invaders, he and other soldiers in his unit were killed in the battle. Qutlugh Khwaja was also seriously wounded, forcing the Mongols to retreat.

In 1301, Alauddin ordered Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan to invade Ranthambore, whose king Hammiradeva had granted asylum to the leaders of the mutiny near Jalore. After Nusrat Khan was killed during the siege, Alauddin personally took charge of the siege operations, and conquered the fort in July 1301. During the Ranthambore campaign, Alauddin faced three unsuccessful rebellions. To suppress any future rebellions, he set up an intelligence and surveillance system, instituted a total prohibition in Delhi, established laws to prevent his nobles from networking with each other, and confiscated wealth from the general public.

In the winter of 1302-1303, Alauddin dispatched an army to ransack the Kakatiya capital Warangal. Meanwhile, he himself led another army to conquer Chittor, the capital of the Guhila kingdom ruled by Ratnasimha. Alauddin captured Chittor after an eight-month long siege. According to his courtier Amir Khusrow, he ordered a massacre of 30,000 local Hindus after this conquest. Some later legends state that Alauddin invaded Chittor to capture Ratnasimha's beautiful queen Padmini, but most modern historians have rejected the authenticity of these legends.

While the imperial armies were busy in Chittor and Warangal campaigns, the Mongols launched another invasion of Delhi around August 1303. Alauddin managed to reach Delhi before the invaders, but did not have enough time to prepare for a strong defence. Meanwhile, the Warangal campaign was unsuccessful (because of heavy rains according to Ziauddin Barani), and the army had lost several men and its baggage. Neither this army, nor the reinforcements sent by Alauddin's provincial governors could enter the city because of the blockades set up by the Mongols. Under these difficult circumstances, Alauddin took shelter in a heavily-guarded camp at the under-construction Siri Fort. The Mongols engaged his forces in some minor conflicts, but neither army achieved a decisive victory. The invaders ransacked Delhi and its neighbourhoods, but ultimately decided to retreat after being unable to breach Siri. The Mongol invasion of 1303 was one of the most serious invasions of India, and prompted Alauddin to take several steps to prevent its repeat. He strengthened the forts and the military presence along the Mongol routes to India. He also implemented a series of economic reforms to ensure sufficient revenue inflows for maintaining a strong army.

Ruins of Somnath in Gujarat (1869)

Ruins of Ranthambore (2014)

Ruins of Chittor (2011)

Ruins of Mandu in Malwa (2013)

In 1304, Alauddin appears to have ordered a second invasion of Gujarat, which resulted in the annexation of the Vaghela kingdom to the Delhi Sultanate. In 1305, Alauddin launched an invasion of Malwa in central India, which resulted in the defeat and death of the Paramara king Mahalakadeva. The Yajvapala dynasty, which ruled the region to the north-east of Malwa, also appears to have fallen to Alauddin's invasion.

In December 1305, the Mongols invaded India again. Instead of attacking the heavily guarded city of Delhi, the invaders proceeded south-east to the Gangetic plains along the Himalayan foothills. Alauddin's 30,000-strong cavalry, led by Malik Nayak, defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Amroha. A large number of Mongols were taken captive and killed; the 16th century historian Firishta claims that the heads (sir) of 8,000 Mongols were used to build the Siri Fort commissioned by Alauddin.

In 1306, another Mongol army sent by Duwa advanced up to the Ravi River, ransacking the territories along the way. Alauddin's forces, led by Malik Kafur, decisively defeated the Mongols. Duwa died next year, and after that the Mongols did not launch any further expeditions to India during Alauddin's reign. On the contrary, Alauddin's Dipalpur governor Malik Tughluq regularly raided the Mongol territories located in present-day Afghanistan.

Marwar and southern campaigns, 1307-1313

Around 1308, Alauddin sent Malik Kafur to invade Devagiri, whose king Ramachandra had discontinued the tribute payments promised in 1296, and had granted asylum to the Vaghela king Karna at Baglana. Kafur was supported by Alauddin's Guarat governor Alp Khan, whose forces invaded Baglana, and captured Karna's daughter Devaladevi (later married to Alauddin's son Khizr Khan). At Devagiri, Kafur achieved an easy victory, and Ramachandra agreed became a lifelong vassal of Alauddin.

Meanwhile, a section of Alauddin's army had been besieging the fort of Siwana in Marwar region unsuccessfully for several years. In August-September 1308, Alauddin personally took charge of the siege operations in Siwana. The Delhi army conquered the fort, and the defending ruler Sitaladeva was killed in November 1308.

Ruins of Devagiri (2016)

Ruins of Warangal (2013)

Ruins of Dwarasamudra (2016)

Ruins of Siwana (2011)

The plunder obtained from Devagiri prompted Alauddin to plan an invasion of the other southern kingdoms, which had accumulated a huge amount of wealth, having been shielded from the foreign armies that had ransacked northern India. In late 1309, he sent Malik Kafur to ransack the Kakatiya capital Warangal. Helped by Ramachandra of Devagiri, Kafur entered the Kakatiya territory in January 1310, ransacking towns and villages on his way to Warangal. After a month-long siege of Warangal, the Kakatiya Prataparudra agreed to become a tributary of Alauddin, and surrendered a large amount of wealth (possibly including the Koh-i-Noor diamond) to the invaders.

Meanwhile, after conquering Siwana, Alauddin had ordered his generals to subjugate other parts of Marwar, before returning to Delhi. The raids of his generals in Marwar led to their confrontations with Kanhadadeva, the Chahamana ruler of Jalore. In 1311, Alauddin's general Malik Kamaluddin Gurg captured the fort after defeating and killing Kanhadadeva.

During the siege of Warangal, Malik Kafur had learned about the wealth of the Hoysala and Pandya kingdoms located further south. After returning to Delhi, he took Alauddin's permission to lead an expedition there. Kafur started his march from Delhi in November 1310, and crossed Deccan in early 1311, supported by Alauddin's tributaries Ramachandra and Prataparudra.

At this time, the Pandya kingdom was reeling under a war of succession between the two brothers Vira and Sundara, and taking advantage of this, the Hoysala king Ballala had invaded the Pandyan territory. When Ballala learned about Kafur's march, he hurried back to his capital Dwarasamudra. However, he could not put up a strong resistance, and negotiated a truce after a short siege, agreeing to surrender his wealth and become a tributary of Alauddin.

From Dwarasamudra, Malik Kafur marched to the Pandya kingdom, where he raided several towns. Both Vira and Sundara fled their headquarters, and thus, Kafur was unable to make them Alauddin's tributaries. Nevertheless, the Delhi army looted a large number of treasures, elephants and horses. The Delhi chronicler Ziauddin Barani described this seizure of wealth from Dwarasamudra and the Pandya kingdom as the greatest one since the Muslim capture of Delhi.

After Ramachandra's death, his son tried to overthrow Alauddin's suzerainty. Malik Kafur invaded Devagiri again in 1313, defeated him, and became the governor of Devagiri.

Accounts of the massacre of Mongols

Mongols from central Asia tried to invade Delhi during the reign of Alauddin many times. Some of these Mongol people also settled near Delhi and accepted Islam. They were called "New Muslims". However, their financial condition was not good. Ala ud-din Khilji suspected them of being involved in a conspiracy to rise against him and of being a threat to his power. In 1298, he ordered them all killed in a single day, and between 15,000 and 30,000 people were slaughtered; the women and children were made slaves.

Political and administrative changes

Alauddin Khilji's administrative and political reforms were based on his conception of fear and control as the basis of good government as well as his military ambitions. The bulk of the measures were designed to centralise power in his hands and to support a large military.

Control over nobility

On his accession to the throne Alauddin khilji had to face a number of revolts by nobles including one by his own nephew, Aqat Khan. Alauddin's response was to increase his level of control over the nobility. He reduced the economic wherewithal of nobels to launch rebellions by confiscating their wealth and removing them from their bases of power. Even charitable lands administered by nobles were confiscated. Severe punishments were given for disloyalty. Even wives and children of soldiers rebelling for greater war spoils were imprisoned. An efficient spy network was set up that reached into the private households of nobles. Marriage alliance made between noble families had to be approved by the king.

Agrarian reforms

The area between Lahore and Dipalpur in the Punjab and Kara (near Allahabad) were removed from the purview of nobles and brought under the direct control of the crown - khalisa. Tax was assessed at half of the output payable in cash. No additional taxes were levied on agriculture. The direct relationship between the cultivator and the state disrupted the power of local landowners that traditionally had power of collecting taxes and parcelling out land within their ares. These landowners had grown prosperous based on their ability to force their share of taxes onto smaller landholders. Under Alauddin, these landowners were forced to pay their own taxes and prevented from passing on that cost to others. The cut landowners made from collecting tax revenue for the state was also abolished. While the cultivators were free from the demands of the landowners, the high taxes imposed by the state meant they had "barely enough for carrying on his cultivation and his food requirements."

To enforce the new system, a strong and efficient revenue administration system was set up. A large number of accountants, collectors, and agents were hired to administer the system. These officials were well-paid but were subject to severe punishment if found to be taking bribes. Account books were audited and even small discrepancies were punished. The effect was both large landowners and small-scale cultivators were fearful of missing out on paying their assessed taxes.

Market reforms and price control

Ala-ud-din Khilji's military ambitions required a standing and strong army, especially after the Mongol siege of Delhi. Maintaining a large army at regular salaries, however, would be severe drain on the treasury. A system of price controls reduced the salary amount that needed to be paid. Three separate markets were set up in Delhi. The first one for food grains, the second for cloth and items such as ghee, oil and sugar. The third market was horses, cattle, and slaves. Regulations were laid out for the operations of these markets. He took various steps to control the prices. He exercised supervisions over the market. He fixed the prices of all the commodities from top to bottom. Market officers called shahna were appointed to keep a check on the prices. The defaulters were heavily punished. Land revenue was fixed and the grain was stored in government granaries.

Tax system

The tax system introduced during the Khalji dynasty had a long term influence on Indian taxation system and state administration.

Alauddin Khalji's taxation system was probably the one institution from his reign that lasted the longest, surviving indeed into the nineteenth or even the twentieth century. From now on, the land tax (kharaj or mal) became the principal form in which the peasant's surplus was expropriated by the ruling class.

— The Cambridge Economic History of India: c.1200-c.1750,

Alauddin Khilji enforced four taxes on non-Muslims in the Sultanate—jizya (poll tax), kharaj (land tax), ghari (house tax) and charah (pasture tax). He also decreed that his Delhi-based revenue officers assisted by local Muslim jagirdars, khuts, mukkadims, chaudharis and zamindars seize by force half of all produce any farmer generates, as a tax on standing crop, so as to fill the sultanate's granaries. His officers enforced tax payment by beating up Hindu and Muslim middlemen responsible for rural tax collection. Furthermore, Alauddin Khilji demanded, state Kulke and Rothermund, from his "wise men in the court" to create "rules and regulations in order to grind down the Hindus, so as to reduce them to abject poverty and deprive them of wealth and any form of surplus property that could foster a rebellion; the Hindu was to be so reduced as to be left unable to keep a horse to ride on, to carry arms, to wear fine clothes, or to enjoy any of the luxuries of life".

Last days

During the last years of his life, Alauddin suffered from an illness, and became very distrustful of his officers. He started concentrating all the power in the hands of his family and his slaves such as Malik Kafur. He removed several experienced administrators, abolished the office of wazir (prime minister), and even executed the minister Sharaf Qa'ini. It appears that Malik Kafur, who considered these officers as his rivals and a threat, convinced Alauddin to carry out this purge.

Ziauddin Barani, who was extremely prejudiced against Kafur (possibly because of his non-Turkic origins), claims that Alauddin "had fallen deeply and madly in love" with Kafur. Kafur had Alauddin's eldest sons Khizr Khan and Shadi Khan blinded. He also convinced Alauddin to order the killing of their father-in-law Alp Khan, an influential noble who could rival Malik Kafur's power. The victims allegedly hatched a conspiracy to overthrow Alauddin, but this might be Kafur's propaganda.

Alauddin died in January 1316. Barani claims that according to "some people", Kafur murdered him.Kafur appointed Alauddin's young son Shihabuddin as a puppet monarch, but Alauddin's elder son Mubarak Khan seized the power shortly after.

Tomb of Alauddin Khilji, Qutb complex, Delhi.

Courts to the east of Quwwat ul-Islam mosque, in Qutb complex added by Khilji in 1300 CE.

Alauddin's Madrasa, Qutb complex, Mehrauli, which also has his tomb to the south.

Alauddin's tomb and madrasa dedicated to him, exists at the back of Qutb complex , Mehrauli, in Delhi India

Religion

Like his predecessors, Alauddin was a Sunni Muslim. His administration persecuted the Isamaili (Shia) minorities, after the orthodox Sunnis falsely accused them of permitting incest in their "secret assemblies". Alauddin ordered an inquiry against them sometime before 1311. The inquiry was conducted by the orthodox ulama, who found several Ismailis guilty. Alauddin ordered the convicts to be sawn into two.

Ziauddin Barani, writing half-a-century after his death, mentions that Alauddin did not patronize the Muslim ulama, and that "his faith in Islam was firm like the faith of the illiterate and the ignorant". Barani further states that Alauddin once thought of establishing a new religion. Just like the Islamic prophet Muhammad's four Rashidun caliphs helped spread Islam, Alauddin believed that he too had four Khans (Ulugh, Nusrat, Zafar and Alp), with whose help he could establish a new religion. Barani's uncle Alaul Mulk convinced him to drop this idea, stating that a new religion could only be found based on a revelation from god, not based on human wisdom. Alaul Mulk also argued that even great conquerors like Genghis Khan had not been able to subvert Islam, and people would revolt against Alauddin for founding a new religion. Barani's claim that Alauddin thought of founding a religion has been repeated by several later chroniclers as well as later historians. Historian Banarsi Prasad Saksena doubts the authenticity of this claim, arguing that it is not supported by Alauddin's contemporary writers.

Alauddin and his generals destroyed several Hindu temples during their military campaigns. These temples included the ones at Bhilsa (1292), Devagiri (1295), Vijapur (1298-1310), Somnath (1299), Jhain in present-day Sawai Madhopur district (1301), Chidambaram (1311) and Madurai (1311). Alauddin compromised with the Hindu chiefs who were willing to accept his suzerainty. In a 1305 document, Amir Khusrau mentions that Alauddin treated the obedient Hindu zamindars (feudal landlords) kindly, and granted more favours to them than they had expected. In his poetic style, Khusrau states that by this time, all the insolent Hindus in the realm of Hind had died on the battlefield, and the other Hindus had bowed their heads before Alauddin. Describing a court held on 19 October 1312, Khusrau writes the ground had become saffron-coloured from the tilaks of the Hindu chiefs bowing before Alauddin. This policy of compromise with Hindus was greatly criticized by a small but vocal set of Muslim extremists, as aparent from Barani's writings.

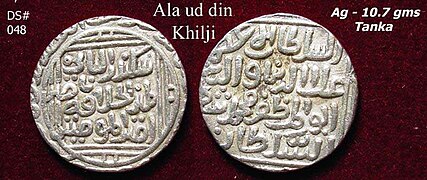

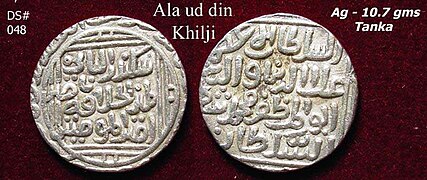

Coins

Copper half Gani

Copper half Gani

Billion Gani

Silver Tanka

Bilingual coin

Silver Tanka Dar al-Islam Mint

Silver Tanka Qila Deogir Mint