Quick Facts

Biography

William Learned Marcy (December 12, 1786 – July 4, 1857) was an American statesman, who served as U.S. Senator, Governor of New York, U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of State. In the latter office (1853–1857) under President Franklin Pierce, he resolved a dispute about the status of U.S. immigrants abroad and negotiated the last major acquisition of land for the continental United States (Gadsden Purchase). He also directed U.S. diplomats to dress in the plain style of an ordinary American rather than the court-dress many had adopted from Europe.

Early life

William Learned Marcy was born in Southbridge, Massachusetts. He graduated from Brown University in 1808, taught school in Dedham, Massachusetts and in Newport, Rhode Island. He read the law and was admitted to the bar in 1811. He moved to Troy, New York, where he began a practice, across the river from the state capital of Albany. Marcy served in the War of 1812, serving first as a lieutenant and afterwards as a captain of volunteers. On October 22, 1812 he took part in the storming of the British post at St. Regis, Canada.

Afterward he served as Recorder of Troy for several years. As he sided with the Anti-Clinton faction of the Democratic-Republican Party, known as the Bucktails, he was removed from office in 1818 by his political opponents. He was the editor of the Troy Budget newspaper.

On April 28, 1824, he married Cornelia Knower (1801–1889, daughter of Benjamin Knower) at the Knower House in Guilderland, New York. They had two surviving children Edmund Marcy (b. ca. 1833) and Cornelia Marcy (1834–1888).

State politics

Marcy became the leading member of the Albany Regency, a group of Democratic politicians who controlled State politics between 1821 and 1838. He was Adjutant General of New York from 1821 to 1823, New York State Comptroller from 1823 to 1829, and an associate justice of the New York Supreme Court from 1829 to 1831.

In 1831, he was elected U.S. Senator from New York by the state legislature as a Jacksonian Democrat, and served from March 4, 1831, to January 1, 1833. He resigned upon taking office as governor, to which position he was elected in 1832. He sat on the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary in the 22nd Congress. Defending Jackson's nomination of Martin Van Buren as minister to the United Kingdom in 1832, Marcy used the phrase "'to the victor belong the spoils," from which the term spoils system is derived to refer to patronage political appointments.

Marcy was elected as Governor of New York for three terms, from 1833 until 1838. In 1838, he was defeated by Whig William H. Seward, which led to a radical change in state politics and then ended the Regency. To the abolitionists who questioned the candidates for governor, Marcy was considered a "doughface," a man with Southern sympathies. He was well aware of the importance of Southern cotton and trade for New York state, both as a major part of exports from New York City, and to the textile mills of upstate that processed cotton from the Deep South.

Marcy was appointed as a member of the Mexican Claims Commission, serving from 1839 to 1842. Later he was recognized as one of the leaders of the Hunkers, the conservative, office-seeking, and pro-compromise-on-slavery faction of the Democratic Party in New York.

Federal politics

Marcy served as United States Secretary of War in the Cabinet of President James K. Polk from 1845 until 1849, when he resumed the practice of law in New York. After 1849, Marcy led the "Soft" faction of the Hunkers that supported reconciliation with the Barnburners. He sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1852 but was unsuccessful, in part by "Hard" opposition led by Daniel S. Dickinson.

Marcy returned to public life in 1853 to serve as United States Secretary of State under President Franklin Pierce. On June 1 of that year, he issued a circular to American diplomatic agents abroad, recommending that whenever practicable, they should appear in the simple dress of an American citizen. This directive created much discussion in Europe, where diplomats typically wore court dress. In 1867, Marcy's recommendation was enacted into law by the US Congress.

Marcy resolved the Koszta Affair (1853), related to detention of an unnaturalized American resident by Austria, gaining his freedom. He negotiated the Gadsden Purchase from Mexico in the Southwest, the last major land acquisition by the United States within its continental territory. It added land to what are now the states of New Mexico and Arizona. With a southern route of territory all under United States control, southerners worked to promote a railroad from Texas to San Diego but were not successful.

Other affairs that demanded Marcy's attention were a Canadian reciprocity treaty, Commodore Matthew C. Perry's negotiations for naval and trade access with Japan, a British fishery dispute, and the Ostend Manifesto.

Marcy died at Ballston Spa, New York on July 4, 1857. He was buried at the Rural Cemetery in Albany, New York.

Legacy and honors

- The United States Revenue Cutter William L. Marcy, launched in 1853, was named in his honor.

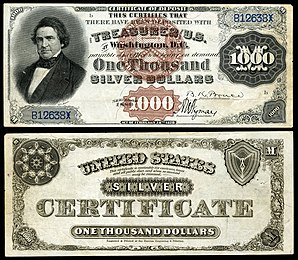

- His portrait appeared on American paper currency, the U.S. $1000 Silver Certificate, issued between 1878 and 1891.

- Mount Marcy in Essex County, at 1629 meters the highest peak in New York, was named for him.

- The Town of Marcy in Oneida County was named for him.

- The Marcy Projects, public housing in Brooklyn, New York, were named for him.

Quotes

"The United States consider powerful navies and large standing armies as permanent establishments to be detrimental to national prosperity and dangerous to civil liberty. The expense of keeping them up is burdensome to the people; they are in some degree a menace to peace among nations. A large force ever ready to be devoted to the purposes of war is a temptation to rush into it. The policy of the United States has ever been, and never more than now, adverse to such establishments, and they can never be brought to acquiesce in any change in International Law which may render it necessary for them to maintain a powerful navy or large standing army in time of peace." — as U.S. Secretary of State, explaining why the United States would not sign the Treaty of Paris.