Quick Facts

Biography

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov (Russian: Варла́м Ти́хонович Шала́мов; June 18, 1907 – January 17, 1982), baptized as Varlaam, was a Russian writer, journalist, poet and Gulag survivor.

Biography

Varlam Shalamov was born in Vologda, Vologda Governorate, a Russian city with a rich culture famous for its wooden architecture, to the family of a hereditary Russian Orthodox priest and teacher, Father Tikhon Nikolayevich Shalamov, a graduate of the Vologda Seminary. At first young Shalamov was named and baptized after the patron of Vologda, Saint Varlaam Khutinskiy (1157–1210); Shalamov later changed his name to the more common Varlam. Shalamov's mother, Nadezhda (Nadia) Aleksandrovna, was a teacher as well. She also enjoyed poetry, and Varlam speculated that she could have become a poet if not for her family. His father worked as a missionary in Alaska for 12 years from 1892, and Varlam's older brother, Sergei, grew up there (he volunteered for World War I and was killed in action in 1917); they returned as events were heating up in Russia by 1905. In 1914, Varlam entered the gymnasium of St. Alexander's and graduated in 1923. After the October Revolution the Soviet regime confiscated Shalamov's house that stands right behind the local church to this day.

Upon his graduation it became clear that the Regional Department of People's Education (RONO, Regionalnoe Otdelenie Narodnogo Obrazovania) would not support his further education because Varlam was a son of a priest. Therefore, he found a job as a tanner at the leather factory in the settlement of Kuntsevo (a suburb of Moscow, since 1960 part of the Moscow city). In 1926, after having worked for two years, he was accepted into the department of Soviet Law at Moscow State University through open competition. While studying there Varlam was intrigued by the oratory skills displayed during the debates between Anatoly Lunacharsky and Metropolitan Alexander Vvedensky. At that time Shalamov was convinced that he would become a literature specialist.

First arrest

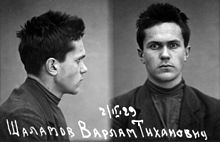

Shalamov joined a Trotskyist-leaning group and on February 19, 1929, was arrested and sent to Butyrskaya prison for solitary confinement. He was later sentenced to three years of correctional labor in the town of Vizhaikha, convicted of distributing the "Letters to the Party Congress" known as Lenin's Testament, which were critical of Joseph Stalin, and of participating in a demonstration marking the tenth anniversary of the Soviet revolution with the slogan "Down with Stalin". Courageously he refused to sign the sentence branding him a criminal. By train he was taken to the former Solikamsk monastery (Solikamsk), which was transformed into a militsiya headquarters of the Vishera department of Solovki ITL OGPU (VishLAG). Shalamov was released in 1931 and worked in the new town of Berezniki, Perm Oblast at the local chemical plant construction site. He was given the opportunity to travel to Kolyma for colonization. Sarcastically, Shalamov said that he would go there only under enforced escort, but, ironically, fate would hold him to his promise later. He returned to Moscow in 1932, where he worked as a journalist and managed to see some of his essays and articles published, including his first short story "The three deaths of Doctor Austino" (1936).

Second arrest

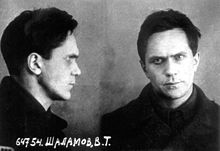

At the outset of the Great Purge, on January 12, 1937, Shalamov was arrested again for "counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities" and sent to Kolyma, also known as "the land of white death," for five years. He was already in jail awaiting sentencing when one of his short stories was published in the literary journal Literary Contemporary. In 1943 he was sentenced to another term, this time for 10 years, under Article 58 (anti-Soviet agitation): the crime was calling Ivan Bunin a "classic Russian writer." The conditions he endured were extreme, first in gold mining operations, and then in coal mining. He was repeatedly sent to punishment zones, both for his political "crimes" and for his attempt to escape. There he managed to survive while sick with typhus of which Shalamov was not aware until he became well. At that time, as he recollects in his writings, he did not care much about his survival.

In 1946, while becoming a dokhodyaga (an emaciated and devitalized state, which in Russian literally means one who is walking towards the ultimate end), his life was saved by a doctor-inmate A.I. Pantyukhov, who risked his own life to get Shalamov a place as a camp hospital attendant. The new "career" allowed Shalamov to survive and concentrate on writing poetry.

After release

In 1951, Shalamov was released from the camp, and continued working as a medical assistant for the forced labor camps of Sevvostlag while still writing. After his release, he was faced with the dissolution of his former family, including a grown-up daughter who now refused to recognize her father. In 1952, Shalamov sent his poetry to Boris Pasternak, who praised his work. Shalamov was allowed to leave Magadan in November 1953 following Stalin's death in March of that year, and was permitted to go to the village of Turkmen in Kalinin Oblast, near Moscow, where he worked as a supply agent.

The Kolyma Tales

From 1954 to 1973, Shalamov worked on his book of short stories of labour camp life, Kolyma Tales. During the Khrushchev thaw, enormous numbers of inmates were released from the Gulag and rehabilitated. Also, many were rehabilitated posthumously. Shalamov was allowed to return to Moscow after having been officially exonerated ("rehabilitated") in 1956. In 1957, he became a correspondent for the literary journal Moskva, and his poetry began to be published. His health, however, had been broken by his years in the camps, and he received an invalid's pension.

Shalamov proceeded to publish poetry and essays in the major Soviet literary magazines while writing his magnum opus, Kolyma Tales. He was acquainted with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Boris Pasternak, and Nadezhda Mandelstam. The manuscripts of Kolyma Tales were smuggled abroad and distributed via samizdat. The translations were published in the West in 1966. The complete Russian-language edition was published in London in 1978, and reprinted thereafter both in Russian and in translation. As the Soviet scholar David Satter writes, "Shalamov's short stories are the definitive chronicle of those camps." Kolyma Tales is considered to be one of the great Russian collections of short stories of the twentieth century.

Gospodin Solzhenitsyn, I willingly accept Your funeral joke on the account of my death. With the feeling of honor and pride I consider myself the first Cold War victim which have fallen from Your hand … – From the undispatched letter of V. T. Shalamov to A. I. Solzhenitsyn

Shalamov also wrote a series of autobiographical essays that vividly bring to life Vologda and his life before prison.

Last years

Western publishers always provided the disclaimer that Shalamov's stories were being published without the author's knowledge or consent. As his health deteriorated, he spent the last three years of his life in a house for elderly and disabled writers of Litfond in Tushino. The quality of this nursing home can be judged from the memoirs of E. Zakharova, who was close to Shalamov in the last six months of his life:

"This kind of places - this is the worst and most obvious evidence of deformation of the human mind, which happened in our country in the 20th century. Man is not only deprived of the right to a decent life, but also to die with dignity."

Shalamov died on January 17, 1982, and was interred at Kuntsevo Cemetery, Moscow. Valery Yesipov wrote that only forty people attended Shalamov’s funeral not counting plainclothes policemen.

Kolyma Tales was finally published on Russian soil in 1987, as a result of Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost policy. Selections from the volume are now mandatory reading for high school children in the Russian Federation.

Legacy

In 1991, the Shalamov family house in Vologda, next to the town's cathedral, was turned into the Shalamov Memorial Museum and local art gallery. The cathedral hill in Vologda has been named in his memory.

One of the Kolyma short stories, "The Final Battle of Major Pugachoff," was made into a film (Последний бой майора Пугачёва) in 2005. In 2007, Russian Television produced the series "Lenin's Testament"(ru:Завещание Ленина), based on Kolyma Tales. A minor planet 3408 Shalamov discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1977 is named after him. A memorial to Shalamov was erected in Krasnovishersk in June 2007, the site of his first labor camp.

Shalamov's friend, Fedot Fedotovich Suchkov, erected a monument on the burial plot, which was destroyed by unknown vandals in 2001. The criminal case was closed as uncompleted. With the help of some workers from SeverStal the monument was reestablished in 2001.

A few of Shalamov's poems were set to music and performed as songs

Several of My Lives

Alexandra Sviridova directed a "documentary" film about Varlam Shalamov in which the narrator, speaking as Shalamov himself, describes life after the October Revolution by simply mentioning facts in chronological sequence. The film starts with a scene that shows a labor camp cemetery with simple wooden sticks placed in the ground to mark burials, with tin lids hanging from them. The narrator says: "Everybody has died." Then he reads a list of names, some of them very famous in their time, of people who, like the narrator, were sent to the camps:

- Nikolay Barbe - the organizer of the Russian Komsomol was shot for being unable to accomplish the Five-Year Plan

- Dmitriy Orlov - Kirov's referent

- Semyon Alekseevich Sheinin - economist

- Ivan Fediakhin - the organizer of the first kolkhoz in Russia and for organization of which he was sentenced

- Fritz David (Ilya-David Israilevich Kruglyansky, 1897·1936; communist, member of the Comintern, lost his mind out of hunger. Member of the Communist Party of Germany, trade union editor of Die Rote Fahne. Sentenced to death in the first of the Moscow show trials in August 1936.

- Yukin - the brigadier of peasants was shot together with his brigade at the Serpentine route

The narrator then states that he has a great doubt whether anybody would be interested in this sad story of a trampled soul. He says that he has lived for 70 years, 20 of which were spent in camps and in exile. Then he starts the story of Shalamov's life.

Publications

- ISBN 0-14-018695-6 Kolyma Tales

- ISBN 0-393-01476-2 Graphite

- ISBN 5-17-004492-5 Vospominaniia (memoirs)

- Varlam Shalamov (1998) "Complete Works" (Варлам Шаламов. Собрание сочинений в четырех томах), printed by publishers Vagrius and Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, ISBN 5-280-03163-1, ISBN 5-280-03162-3