Quick Facts

Biography

Okumura Masanobu (Japanese: 奥村 政信; 1686 – 13 March 1764) was a Japanese print designer, book publisher, and painter. He also illustrated novelettes and in his early years wrote some fiction. At first his work adhered to the Torii school, but later drifted beyond that. He is a figure in the formative era of ukiyo-e doing early works on actors and bijin-ga ("pictures of beautiful women").

Life and career

While Masanobu's early life is largely undocumented, he is believed to have been born about 1686, possibly in Edo (modern Tokyo). Edo was a small fishing village when it was Tokugawa Ieyasu chose it as his administrative capital of the Tokugawa shogunate, and by the early 17th century the city had prospered and its population had grown to half a million.

Masanobu appears to have been self-taught; he is not known to have belonged to any artistic school. His early work shows the influence of the Torii school of ukiyo-e painting, particularly Torii Kiyonobu I, and he likely learned from the examples of Torii Kiyomasa and the early ukiyo-e artist Hishikawa Moronobu. A print album published by Kurihara Chōemon in 1701 depicting coutesans in the Yoshiwara pleasure district is Masanobu's earliest surviving signed work, followed by a similar work ten months later. Moronobu provided the illustrations, and sometimes text, for at least twenty-two ukiyo-zōshi novels and librettos for puppet theatre between 1703 and 1711. These included a modernized illustrated version of the 11th-century Tale of Genji in eighteen volumes, whose translation was by Masanobu.

After 1711 Masanobu's output of book illustrations shriveled as he turned his attention to albums of prints, usually about a dozen per set, on a variety of themes—most outstanding of which were the comic albums. These prints, influenced perhaps by 12th-century Toba-e and the caricature paintings of Hanabusa Itchō (1652–1724), depicted humorous scenes from, or parodies of, Noh, kabuki, and Japanese mythology. This period also saw Masanobu produce large kakemono-sized portraits of courtesans, whose designs had a warmth and humanity largely absent from the earlier Torii and Kaigetsudō beauties. The financial restraints of the Kyōhō reforms begun in 1717 brought an end to the luxury of these large prints, replaced by smaller hosoban-sized prints, which were often sold as triptychs—which when placed together were little smaller than the kakemono-sized prints. At least as early as 1718, Masanobu's were some of the earliest urushi-e prints, printed with brass powder sprinkled on the ink, which created a lacquer effect.

About 1721 Masanobu abandoned the publishers of his earlier works and opened his own wholesaler, Okumura-ya, in Tōri Shio-chō in Edo. His trade mark was a gourd-shaped sign, a mark he thereafter stamped on the works he printed.

It is likely that Masanobu died at 78 in 1764; 1769 has also been given as his death date.

Art styles

Okumura Masanobu is said to be master of the Urushi-e style. Urushi-e is usually done on woodblocks and has thick black lines. Styles of Urushi-e can be found in many works from Okumura Masanobu but the most famous examples would be; Large Perspective View of the Interior of Echigo-ya in Suruga-chô, Actor holding folders, Actor as Wakanoura Osana Komachi, Actors Ôtani Hiroji and Sodesaki Iseno, and Lion, Peonies, and Rock. All of these works have dark, thick lines and are made on woodblocks. His works are also famous for his gentile and flowing lines he uses throughout his drawings. He also has a reoccurring pattern throughout his works consisting of tan backgrounds and neutral coloring. His pieces capture things and or people in motion. His objects in the drawings are always in mid motion of walking somewhere or doing something; definitely not pictures of still drawings. Masanobu was also famous for capturing the beauty of nature. He would paint/draw; birds, women, men, actors, and warriors. The style of the Japanese women he draws in his pieces all have the same style and ‘boneless’ structure. The face is showing, however, the bodies are covered up by long flowing dresses. This style is referred to as Tan-e, which means he draws women as full bodied and round6. The tan-e style brings a sense of gentleness to the beauties and gracefulness. Okumura Masanobu’s art works also consist of the insights of stores and theatres. These pieces are large-scare and referred to as; uki-e. Uki-e is a style used by Japanese artists that means “looming picture” 2. He was very good at capturing the luxury and leisure of his paintings on theatre. He also played around and experimented with all kinds of styles on woodprints and was always willing to learn more. By experimenting, he created and said to be the first artist to make pillar prints. Okumura is also said to be the creator of the large wide, vertical sized prints referred to as habahiro hashira-e, also2. Many of his scripts are examples of this style of print. Masanobu was known for staying true to his time and what he was good at. He created many new styles that are still being used today and without him; art wouldn’t be the same2.

While most of his works were prints, Masanobu also produced ukiyo-e paintings. Mostly produced in the Kyōhō era, they display the printmaker's sense of line, colour, and composition. Thesubjects are most often humorous, and are executed in a lively manner with figures in brightly coloured, fashionable clothing.

- Works by Okumura Masanobu

A Roofer's Precariousness

Daytime in the Gay Quarters

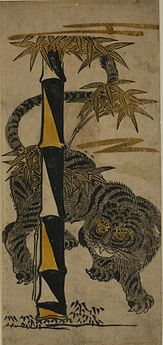

Tiger and Bamboo, c. 1725

- Uki-e by Okumura Masanobu

Morita-za

Taking the Evening Cool by Ryōgoku Bridge, 1745

Shibai Uki-e, c. 1741–44

Legacy

The era Masanobu was born into was a prosperous and creatively fertile one, in which flourished the haiku poets Matsuo Bashō and Ihara Saikaku, the bunraku dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon, and the painter Ogata Kōrin. Masanobu was one of the most influential innovators of the ukiyo-e form, introducing the comic album, the pillar, two-colour, and lacquer prints, and popularizing Western-style perspective drawing. His career saw ukiyo-e evolve from its monochromatic origins to the verge of the full-colour nishiki-e revolution of Suzuki Harunobu's time.

Though less known to the public than masters such as Sharaku and Hokusai, Masanobu has gained the regard of connoisseurs as one of the greatest ukiyo-e artists, held in esteem by Japanese collectors such as Kiyoshi Shibui and Seiichirō Takahashi, and Westerners such as Ernest Fenollosa, Arthur Davison Ficke, and James A. Michener.