Marcus Garvey

Quick Facts

Biography

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. ONH (17 August 1887 – 10 June 1940) was a Jamaican-born political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL, commonly known as UNIA), through which he declared himself Provisional President of Africa. Ideologically a black nationalist and Pan-Africanist, his ideas came to be known as Garveyism.

Garvey was born to a moderately prosperous Afro-Jamaican family in Saint Ann's Bay, Colony of Jamaica and apprenticed into the print trade as a teenager. Working in Kingston, he became involved in trade unionism before working briefly in Costa Rica, Panama, and England. Returning to Jamaica, he founded UNIA in 1914. In 1916, he moved to the United States and established a UNIA branch in Harlem. Emphasising unity between Africans and the African diaspora, he campaigned for an end to European colonial rule across Africa and the political unification of the continent. He envisioned a unified Africa as a one-party state, governed by himself, that would enact laws to ensure black racial purity. Although he never visited the continent, he was committed to the Back-to-Africa movement, arguing that many African-Americans should migrate there. UNIA grew in membership and Garveyist ideas became increasingly popular. However, his black separatist views—and his collaboration with white racist groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) to advance their shared interest in racial separatism—divided Garvey from other prominent African-American civil rights activists such as W. E. B. Du Bois who promoted racial integration.

Committed to the belief that African-Americans needed to secure financial independence from white-dominant society, Garvey launched various businesses in the U.S., including the Negro Factories Corporation. In 1919, he became President of the Black Star Line shipping and passenger company, designed to forge a link between North America and Africa and facilitate African-American migration to Liberia. After it went bankrupt, in 1923 Garvey was convicted of mail fraud for selling its stock and imprisoned. Many commentators have argued that the trial was politically motivated; Garvey blamed Jewish people, claiming that they were prejudiced against him because of his links to the KKK. Deported to Jamaica in 1927, Garvey continued his activism and established the People's Political Party in 1929. As well as launching the Edelweiss Amusement Company, he continued to travel internationally to promote UNIA, presenting his Petition of the Negro Race to the League of Nations in Geneva. In 1935 he relocated to London, where his anti-socialist stance distanced him from many of the city's black activists. He died there in 1940, although in 1964 his body was returned to Jamaica for reburial in Kingston's National Heroes Park.

Garvey was a controversial figure. Many in the African diasporic community regarded him as a pretentious demagogue and were highly critical of his collaboration with white supremacists, his violent rhetoric, and his prejudice towards mixed-race people. He nevertheless received praise for encouraging a sense of pride and self-worth among Africans and the African diaspora amid widespread poverty, discrimination, and colonialism. He is seen as a national hero in Jamaica, and his ideas exerted a considerable influence on movements like Rastafari, the Nation of Islam, and the Black Power Movement.

Early life

Childhood: 1887–1904

Marcus Mosiah Garvey was born on 17 August 1887 in Saint Ann's Bay, a town in the Colony of Jamaica. In the context of colonial Jamaican society, which had a colourist social hierarchy, Garvey was considered at the lowest end, being a black child who believed he was of full African ancestry; later genetic research nevertheless revealed that he had some Iberian ancestors. Garvey's paternal grandfather and great-grandfather had been born into slavery prior to its abolition in the British Empire. His surname, which was of Irish origin, had been inherited from his family's former owners.

His father, Malchus Garvey, was a stonemason; his mother, Sarah Richards, was a domestic servant and the daughter of peasant farmers. Malchus had had two previous partners before Sarah, siring six children between them. Sarah bore him four additional children, of whom Marcus was the youngest, although two died in infancy. Because of his profession, Malchus' family were wealthier than many of their peasant neighbours; they were petty bourgeoise. Malchus was however reckless with his money and over the course of his life lost most of the land he owned to meet payments. Malchus had a book collection and was self-educated; he also served as an occasional layman at a local Wesleyan church. Malchus was an intolerant and punitive father and husband; he never had a close relationship with his son.

Up to the age of 14, Garvey attended a local church school; further education was unaffordable for the family. When not in school, Garvey worked on his maternal uncle's tenant farm. He had friends, with whom he once broke the windows of a church, resulting in his arrest. Some of his friends were white, although he found that as they grew older they distanced themselves from him; he later recalled that a close childhood friend was a white girl: "We were two innocent fools who never dreamed of a race feeling and problem." In 1901, Marcus was apprenticed to his godfather, a local printer. In 1904, the printer opened another branch at Port Maria, where Garvey began to work, traveling from Saint Ann's Bay each morning.

Early career in Kingston: 1905–1909

In 1905 he moved to Kingston, where he boarded in Smith Village, a working class neighbourhood. In the city, he secured work with the printing division of the P.A. Benjamin Manufacturing Company. He rose quickly through the company ranks, becoming their first Afro-Jamaican foreman. His sister and mother, by this point estranged from his father, moved to join him in the city. In January 1907, Kingston was hit by an earthquake that reduced much of the city to rubble. He, his mother, and his sister were left to sleep in the open for several months. In March 1908, his mother died. While in Kingston, Garvey converted to Roman Catholicism.

Garvey became a trade unionist and took a leading role in the November 1908 print workers' strike. The strike was broken several weeks later and Garvey was sacked. Henceforth branded a troublemaker, Garvey was unable to find work in the private sector. He then found temporary employment with a government printer. As a result of these experiences, Garvey became increasingly angry at the inequalities present in Jamaican society.

Garvey involved himself with the National Club, Jamaica's first nationalist organisation, becoming its first assistant secretary in April 1910. The group campaigned to remove the British Governor of Jamaica, Sydney Olivier, from office, and to end the migration of Indian "coolies", or indentured workers, to Jamaica, as they were seen as a source of economic competition by the established population. With fellow Club member Wilfred Domingo he published a pamphlet expressing the group's ideas, The Struggling Mass. In early 1910, Garvey began publishing a magazine, Garvey's Watchman—its name a reference to George William Gordon's The Watchman—although it only lasted three issues. He claimed it had a circulation of 3000, although this was likely an exaggeration. Garvey also enrolled in elocution lessons with the radical journalist Robert J. Love, whom Garvey came to regard as a mentor. With his enhanced skill at speaking in a Standard English manner, he entered several public speaking competitions.

Travels abroad: 1910–1914

Economic hardship in Jamaica led to growing emigration from the island. In mid-1910, Grant travelled to Costa Rica, where an uncle had secured him employment as a timekeeper on a large banana plantation in the Limón Province owned by the United Fruit Company (UFC). Shortly after his arrival, the area experienced strikes and unrest in opposition to the UFC's attempts to cut its workers' wages. Although as a timekeeper he was responsible for overseeing the manual workers, he became increasingly angered at how they were treated. In the spring of 1911 be launched a bilingual newspaper, Nation/La Nación, which criticised the actions of the UFC and upset many of the dominant strata of Costa Rican society in Limón. His coverage of a local fire, in which he questioned the motives of the fire brigade, resulted in him being brought in for police questioning. After his printing press broke, he was unable to replace the faulty part and terminated the newspaper.

Garvey then travelled through Central America, undertaking casual work as he made his way through Honduras, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela. While in the port of Colón in Panama, he set up a new newspaper, La Prensa ("The Press"). In 1911, he became seriously ill with a bacterial infection and decided to return to Kingston. He then decided to travel to London, the administrative centre of the British Empire, in the hope of advancing his informal education. In the spring of 1912 he sailed to England. Renting a room along Borough High Street in South London, he visited the House of Commons, where he was impressed by the politician David Lloyd George. He also visited Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park and began speaking there. There were only a few thousand black people in London at the time, and they were often viewed as exotic; most worked as labourers. Garvey initially gained piecemeal work labouring in the city's dockyards. In August 1912, his sister Indiana joined him in London, where she worked as a domestic servant.

In early 1913 he was employed as a messenger and handyman for the African Times and Orient Review, a magazine based in Fleet Street that was edited by Dusé Mohamed Ali. The magazine advocated Ethiopianism and home rule for British-occupied Egypt. In 1914, Mohamed Ali began employing Garvey's services as a writer for the magazine. He also took several evening classes in law at Birkbeck College in Bloomsbury. Garvey planned a tour of Europe, spending time in Glasgow, Paris, Monte Carlo, Boulogne, and Madrid. During the trip, he was briefly engaged to a Spanish-Irish heiress. Back in London, he wrote an article on Jamaica for the Tourist magazine, and spent time reading in the library of the British Museum. There he discovered Up from Slavery, a book by the African-American entrepreneur and activist Booker T. Washington. Washington's book heavily influenced him. Now almost financially destitute and deciding to return to Jamaica, he unsuccessfully asked both the Colonial Office and the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines' Protection Society to pay for his journey. After managing to save the funds for a fare, he boarded the SS Trent in June 1914 for a three-week journey across the Atlantic. En route home, Garvey talked with an Afro-Caribbean missionary who had spent time in Basutoland and taken a Basuto wife. Discovering more about colonial Africa from this man, Garvey began to envision a movement that would politically unify black people of African descent across the world.

Organization of UNIA

Forming UNIA: 1914–1916

— Garvey, from a 1915 Collegiate Hall speech published in the Daily Chronicle

Garvey arrived back in Jamaica in July 1914. There, he saw his article for Tourist republished in The Gleaner. He began earning money selling greeting and condolence cards which he had imported from Britain, before later switching to selling tombstones.

Also in July 1914, Garvey launched the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, commonly abbreviated as UNIA. Adopting the motto of "One Aim. One God. One Destiny", it declared its commitment to "establish a brotherhood among the black race, to promote a spirit of race pride, to reclaim the fallen and to assist in civilising the backward tribes of Africa." Initially, it had only few members. Many Jamaicans were critical of the group's prominent use of the term "Negro", a term which was often employed as an insult: Garvey, however, embraced the term in reference to black people of African descent.

Garvey became UNIA's president and travelling commissioner; it was initially based out of his hotel room in Orange Street, Kingston. It portrayed itself not as a political organisation but as a charitable club, focused on work to help the poor and to ultimately establish a vocational training college modelled on Washington's Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Garvey wrote to Washington and received a brief, if encouraging reply; Washington died shortly after. UNIA officially expressed its loyalty to the British Empire, King George V, and the British effort in the ongoing First World War. In April 1915 Brigadier General L. S. Blackden lectured to the group on the war effort; Garvey endorsed Blackden's calls for more Jamaicans to sign up to fight for the Empire on the Western Front. The group also sponsored musical and literary evenings as well as a February 1915 elocution contest, at which Garvey took first prize.

In August 1914, Garvey attended a meeting of the Queen Street Baptist Literary and Debating Society, where he met Amy Ashwood, recently graduated from the Westwood Training College for Women. She joined UNIA and rented a better premises for them to use as their headquarters, secured using her father's credit. She and Garvey embarked on a relationship, which was opposed by her parents. In 1915 they secretly became engaged. When she suspended the engagement, he threatened to commit suicide, at which she resumed it.

— Garvey, on how he was received in Jamaica

Garvey attracted financial contributions from many prominent patrons, including the Mayor of Kingston and the Governor of Jamaica, William Manning. By appealing directly to Jamaica's white elite, Garvey had skipped the brown middle-classes, comprising those who were classified as mulattos, quadroons, and octoroons. They were generally hostile to Garvey, regarding him as a pretentious social climber and being annoyed at his claim to be part of the "cultured class" of Jamaican society. Many also felt that he was unnecessarily derogatory when describing black Jamaicans, with letters of complaint being sent into the Daily Chronicle after it published one of Garvey's speeches in which he referred to many of his people as "uncouth and vulgar". One complainant, a Dr Leo Pink, related that "the Jamaican Negro can not be reformed by abuse". After unsubstantiated allegations began circling that Garvey was diverting UNIA funds to pay for his own personal expenses, the group's support began to decline. He became increasingly aware of how UNIA had failed to thrive in Jamaica and decided to migrate to the United States, sailing there aboard the SS Tallac in March 1916.

To the United States: 1916–1918

Arriving in the United States, Garvey began lodging with a Jamaican expatriate family living in Harlem, a largely black area of New York City. He began lecturing in the city, hoping to make a career as a public speaker, although at his first public speech was heckled and fell off the stage. From New York City, he embarked on a U.S. speaking tour, crossing 38 states. At stopovers on his journey he listened to preachers from the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the Black Baptist churches. While in Alabama, he visited the Tuskegee Institute and met with its new leader, Robert Russa Moton. After six months traveling across the U.S. lecturing, he returned to New York City.

In May 1917, Garvey launched a New York branch of UNIA. He declared membership open to anyone "of Negro blood and African ancestry" who could pay the 25 cents a month membership fee. He joined many other speakers who spoke on the street, standing on step-ladders; he often did so on Speakers' Corner in 135th Street. In his speeches, he sought to reach across to both black West Indian migrants like himself and native African-Americans. Through this, he began to associate with Hubert Harrison, who was promoting ideas of black self-reliance and racial separatism. In June, Garvey shared a stage with Harrison at the inaugural meeting of the latter's Liberty League of Negro-Americans. Through his appearance here and at other events organised by Harrison, Garvey attracted growing public attention.

After the U.S. entered the First World War in April 1917, Garvey initially signed up to fight but was ruled physically unfit to do so. He later became an opponent of African-American involvement in the conflict, following Harrison in accusing it of being a "white man's war". In the wake of the East St. Louis Race Riots in May to July 1917, in which white mobs targeted black people, Garvey began calling for armed self-defense. He produced a pamphlet, "The Conspiracy of the East St Louis Riots", which was widely distributed; proceeds from its sale went to victims of the riots. The Bureau of Investigation began monitoring him, noting that in speeches he employed more militant language than that used in print; it for instance reported him expressing the view that "for every Negro lynched by whites in the South, Negroes should lynch a white in the North."

By the end of 1917, Garvey had attracted many of Harrison's key associates in his Liberty League to UNIA. He also secured the support of the journalist John Edward Bruce, agreeing to step down from the group's presidency in favor of Bruce. Bruce then wrote to Dusé Mohamed Ali to learn more about Garvey's past. Mohamed Ali responded with a negative assessment of Garvey, suggesting that he simply used UNIA as a money-making scheme. Bruce read this letter to a UNIA meeting and put pressure on Garvey's position. Garvey then resigned from UNIA, establishing a rival group that met at Old Fellows Temple. He also launched legal proceedings against Bruce and other senior UNIA members, with the court ruling that the group's name and membership—now estimated at around 600—belonged to Garvey, who resumed control over it.

The growth of UNIA: 1918–1921

In 1918, UNIA membership grew rapidly. In June that year it was incorporated, and in July a commercial arm, the African Communities' League, filed for incorporation. Garvey envisioned UNIA establishing an import-and-export business, a restaurant, and a launderette. He also proposed raising the funds to secure a permanent building as a base for the group. In April 1918, Garvey launched a weekly newspaper, the Negro World, which Cronon later noted remained "the personal propaganda organ of its founder". Financially, it was backed by philanthropists like Madam C. J. Walker, but six months after its launch was pursuing a special appeal for donations to keep it afloat. Various journalists took Garvey to court for his failure to pay them for their contributions, a fact much publicised by rival publications; at the time, there were over 400 black-run newspapers and magazines in the U.S. Unlike may of these, Garvey refused to feature adverts for skin-lightening and hair-straightening products, urging black people to "take the kinks out of your mind, instead of out of your hair". By the end of its first year, the circulation of Negro World was nearing 10,000; copies circulated not only in the US, but also in the Caribbean, Central, and South America.

Garvey appointed his old friend Domingo, who had also arrived in New York City, as the newspaper's editor. However, Domingo's socialist views alarmed Garvey who feared that they would imperil UNIA. Garvey had Domingo brought before UNIA's nine-person executive committee, where he was accused of writing editorials professing ideas at odds with UNIA's message. Domingo resigned several months later; he and Garvey henceforth became enemies. In September 1918, Ashwood sailed from Panama to be with Garvey, arriving in New York City in October. In November, she became General Secretary of UNIA. At UNIA gatherings, she was responsible for reciting black-authored poetry, as was the actor Henrietta Vinton Davis, who had also joined the movement.

After the First World War ended, President Woodrow Wilson declared his intention to present a 14-point plan for world peace at the forthcoming Paris Peace Conference. Garvey was among the African-Americans who formed the International League of Darker Peoples which sought to lobby Wilson and the conference to give greater respect to the wishes of people of colour; their delegates nevertheless were unable to secure the travel documentation. At Garvey's prompting, UNIA sent a young Haitian, Elizier Cadet, as its delegate to the conference. The world leaders who met at the conference nevertheless largely ignored such perspectives, instead reaffirming their support for European colonialism.

In the U.S., many African-Americans who had served in the military refused to return to their more subservient role in society and throughout 1919 there were various racial clashes throughout the country. The government feared that black people would be encouraged to revolutionary behavior following the October Revolution in Russia, and in this context, military intelligence ordered Major Walter Loving to investigate Garvey. Loving's report concluded that Garvey was a "very able young man" who was disseminating "clever propaganda". The BOI's J. Edgar Hoover decided that Garvey was worthy of deportation and decided to include him in their Palmer Raids launched to deport subversive non-citizens. The BOI presented Garvey's name to the Labor Department under Louis F. Post to ratify the deportation but Post's department refused to do so, stating that the case against Garvey was not proven.

Success and obstacles

UNIA grew rapidly and in just over 18 months it had branches in 25 U.S. states, as well as divisions in the West Indies, Central America, and West Africa. The exact membership is not known, although Garvey—who often exaggerated numbers—claimed that by June 1919 it had two million members. It remained smaller than the better established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), although there was some crossover in membership of the two groups. The NAACP and UNIA differed in their approach; while the NAACP was a multi-racial organisation which promoted racial integration, UNIA was a black-only group. The NAACP focused its attention on what it termed the "talented tenth" of the African-American population, such as doctors, lawyers, and teachers, whereas UNIA emphasized the image of a mass organisation and included many poorer people and West Indian migrants in its ranks. NAACP supporters accused Garvey of stymieing their efforts at bringing about racial integration in the U.S.

Garvey was dismissive of the NAACP leader W. E. B. Du Bois, and in one issue of the Negro World called him a "reactionary under [the] pay of white men". Du Bois generally tried to ignore Garvey, regarding him as a demagogue, but at the same time wanted to learn all he could about Garvey's movement. In 1921, Garvey twice reached out to DuBois, asking him to contribute to UNIA publications, but the offer was rebuffed. Their relationship became acrimonious; in 1923, DuBois described Garvey as "a little fat black man, ugly but with intelligent eyes and big head". By 1924, Grant suggested, the two hated each other.

To promote his views to a wide audience, Garvey took to shouting slogans from a megaphone as he was driven through Harlem in a Cadillac.UNIA established a restaurant and ice cream parlour at 56 West 135th Street, and also launched a millinery store selling hats. With an increased income coming in through UNIA, Garvey moved to a new residence at 238 West 131st Street; in 1919, a young middle-class Jamaican migrant, Amy Jacques, became his personal secretary. UNIA also obtained a partially-constructed church building in Harlem, which Garvey named "Liberty Hall" after its namesake in Dublin, Ireland, which had been established during the Easter Rising of 1916. The adoption of this name reflected Garvey's fascination for the Irish independence movement. Liberty Hall's dedication ceremony was held in July 1919. Garvey also organised the African Legion, a group of uniformed men who would attend UNIA parades; a secret service was formed from Legion members, providing Garvey with intelligence about group members. The formation of the Legion further concerned the BOI, who sent their first full-time black agent, James Wormley Jones, to infiltrate UNIA. In January 1920, Garvey incorporated the Negro Factories League. According to Grant, a personality cult had grown up around Garvey within the UNIA movement; life-size portraits of him hung in the UNIA HQ and phonographs of his speeches were sold to the membership.

In August, UNIA organized the First International Conference of the Negro Peoples in Harlem. This parade was attended by Gabriel Johnson, the Mayor of Monrovia in Liberia. As part of it, an estimated 25,000 people assembled in Madison Square Gardens. At the conference, UNIA delegates declared him the Provisional President of Africa, charged with heading a government-in-exile. Some of the West Africans attending the event were angered by this, believing it wrong that an Afro-Jamaican, rather than an African, as taking on this role. Many outside the movement ridiculed Garvey for giving himself this title. The conference then elected other members of the African government-in-exile, and resulted in the production of a Bill of Rights which condemned colonial rule across Africa. In August 1921, UNIA held a banquet in Liberty Hall, at which Garvey have out honors to various supporters, including such titles as Order of the Nile and the Order of Ethiopia.

UNIA established growing links with the Liberian government, hoping to secure land in the West African nation where various African-Americans could move to. Liberia was in heavy debt, with UNIA launching a fundraising campaign to raise $2 million towards a Liberian Construction Loan. In 1921, Garvey sent a UNIA team to assess the prospects in Liberia. Internally, UNIA experienced various feuds. Garvey pushed out Cyril Briggs and other members of the African Blood Brotherhood from UNIA, wanting to place growing distance between himself and black socialist groups. In the Negro World, Garvey then accused Briggs—who was of mixed heritage—of being a white man posing as a black man. Briggs then successfully sued Garvey for criminal libel.

Assassination attempts, marriage, and divorce

In July 1919, Garvey was arrested and charged with criminal libel for claims made about Edwin Kilroe in the Negro World. When this eventually came to court, he was ordered to provide a printed retraction. In October 1919, George Tyler, a part-time vendor of the Negro World, entered the UNIA office and tried to assassinate Garvey. The latter received two bullets in his legs but survived. Tyler was soon apprehended but died in an escape attempt from jail; it was thus never revealed who he tried to kill Garvey. Garvey soon recovered from the incident; five days later he gave a public speech in Philadelphia. After the assassination attempt, Garvey hired a bodyguard, Marcellus Strong. Shortly after the incident, Garvey proposed marriage to Ashwood, to which she accepted. On Christmas Day, they had a private Roman Catholic church wedding, followed by a major ceremonial celebration in Liberty Hall, attended by 3000 UNIA members. Jacques was her maid of honour. After the marriage, he moved into Ashwood's apartment.

The newlyweds embarked on a two-week honeymoon in Canada, accompanied by a small UNIA retinue, including Jacques. There, Garvey spoke at two mass meetings in Montreal and three in Toronto. Returning to Harlem, the couple's marriage was soon strained. Ashwood complained of Garvey's growing closeness with Jacques. Garvey was upset by his inability to control his wife, particularly her drinking and her socialising with other men. She was pregnant, although the child was possibly not his; she did not inform him of this, and the pregnancy ended in miscarriage.

Three months into the marriage, Garvey sought an annulment, on the basis of Ashwood's alleged adultery and the claim that she had used "fraud and concealment" to induce the marriage. She launched a counter-claim for desertion, requesting $75 a week alimony. The court rejected this sum, but ordered Garvey to pay her $12 a week, but also refused to grant him the divorce. The court proceedings continued for two years. Now separated, Garvey moved into a 129th Street apartment with Jacques and Henrietta Vinton Davis, an arrangement that at the time could have caused some social controversy. He was later joined there by his sister Indiana and her husband, Alfred Peart. Ashwood, meanwhile, went on to become a lyricist and musical director for musicals amid the Harlem Renaissance.

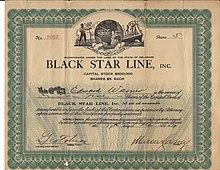

The Black Star Line

From 56 West 135th, UNIA also began selling shares for a new business, the Black Star Line. The Black Star Line based its name on the White Star Line. Garvey envisioned a shipping and passenger line travelling between Africa and the Americas, which would be black-owned, black-staffed, and utilised by black patrons. He thought that the project could be launched by raising $2 million from African-American donors, publicly declaring that any black person who did not buy stock in the company "will be worse than a traitor to the cause of struggling Ethiopia". He incorporated the company and then sought about trying to purchase a ship. Many African-Americans took great pride in buying company stock, seeing it as an investment in their community's future; Garvey also promised that when the company began turning a profit they would receive significant financial returns on their investment. To advertise this stock, he travelled to Virginia, and then in September 1919 to Chicago, where he was accompanied by seven other UNIA members. In Chicago, he was arrested and fined for violating the Blue Sky Laws which banned the sale of stock in the city without a license.

With growing quantities of money coming in, a three-man auditing committee was established, with found that UNIA's funds were poorly recorded and that the company's books were not balanced. This was followed by a breakdown in trust between the directors of the Black Star Line, with Garvey discharging two of them, Richard E. Warner and Edgar M. Grey, and publicly humiliating them as the next UNIA meeting. People continued buying stock regardless and by September 1919, the Black Star Line company had accumulated $50,000 by selling stock. It could thus afford a thirty-year old tramp ship, the SS Yarmouth. The ship was formally launched in a ceremony on the Hudson River on 31 October. The company had been unable to find enough trained black seamen to staff the ship, so its initial chief engineer and chief officer were white.

The ship's first assignment was to sale to Cuba and then to Jamaica, before returning to New York. After that first voyage, the Yarmouth was found to contain many problems and the Black Star Line had to pay $11,000 for repairs. On its second voyage, again to the Caribbean, it hit bad weather shortly after departure and had to be towed back to New York by the coastguard for further repairs. Garvey planned to obtain and launch a second ship by February 1920, with the Black Star Line putting down a $10,000 down payment on a paddle ship called the SS Shadyside. In July 1920, Garvey sacked both the Black Star Line's secretary, Edward D. Smith-Green, and its captain, Cockburn; the latter was accused of corruption. In early 1922, the Yarmouth was sold for scrap metal.

In 1921, Garvey travelled to the Caribbean aboard a new BSL ship, the Antonio Maceo, which they had renamed the Kanawha. While in Jamaica, he criticised its inhabitants as being backward and claimed that "Negroes are the most lazy, the most careless and indifferent people in the world". His comments in Jamaica earned many enemies who criticised him on multiple fronts, including the fact he had left his destitute father to die in an almshouse. Attacks back-and-forth between Garvey and his critics appeared in the letters published by The Gleaner. From Jamaica, Garvey travelled to Costa Rica, where the United Fruit Company assisted his transportation around the country, hoping to gain his favour. There, he met with President Julio Acosta. Arriving in Panama, at one of his first speeches, in Almirante, he was booed after doubling the advertised entry price; his response was to call the crowd "a bunch of ignorant and impertinent Negroes. No wonder you are where you are and for my part you can stay where you are." He received a far warmer reception at Panama City, after which he sailed to Kingston. From there he sought a return to the U.S., but was repeatedly denied an entry visa. This was only granted after he wrote directly to the State Department.

Criminal charges: 1922–1923

In January 1922, Garvey was arrested and charged with mail fraud for having advertised the sale of stocks in a ship, the Orion, which the Black Star Line did not yet own. He was bailed for $2,500. Hoover and the BOI were committed to securing a conviction; they had also received complaints from a small number of the Black Star Line's stock owners, who wanted them to pursue the matter further. Garvey spoke out against the charges he faced, but focused on blaming not the state, but rival African-American groups, for them. As well as accusing disgruntled former members of UNIA, in a Liberty Hall speech, he implied that the NAACP were behind the conspiracy to imprison him. The mainstream press picked up on the charge, largely presenting Garvey as a con artist who had swindled African-American people.

After the arrest, he made plans for a tour of the western and southern states. This included a parade in Los Angeles, partly to woo back members of UNIA's California branch, which had recently splintered off to become independent. In June 1922, Garvey met with Edward Young Clarke, the Imperial Wizard pro tempore of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) at the Klan's offices in Atlanta. Garvey made a number of incendiary speeches in the months leading up to that meeting; in some, he thanked the whites for Jim Crow.Garvey once stated:

I regard the Klan, the Anglo-Saxon clubs and White American societies, as far as the Negro is concerned, as better friends of the race than all other groups of hypocritical whites put together. I like honesty and fair play. You may call me a Klansman if you will, but, potentially, every white man is a Klansman as far as the Negro in competition with whites socially, economically and politically is concerned, and there is no use lying.

News of Garvey's meeting with the KKK soon spread and it was covered on the front page of many African-American newspapers, causing widespread upset. When news of the meeting was revealed, it generated much surprise and anger among African-Americans; Grant noted that it marked "the most significant turning point in his popularity". Several prominent black Americans—Chandler Owen, A. Philip Randolph, William Pickens, and Robert Bagnall—launched the "Garvey Must Go" campaign in the wake of the revelation. Many of these critics played to nativist ideas by emphasising Garvey's Jamaican identity and sometimes calling for his deportation. Pickens and several other of Garvey's critics claimed to have been threatened, and sometimes physically attacked, by Garveyites. Randolph reported receiving a severed hand in the post, accompanied by a letter from the KKK threatening him to stop criticising Garvey and to join UNIA.

—Garvey's telegram to UNIA HQ, June 1922.

1922 also brought some successes for Garvey. He attracted the country's first black pilot, Hubert Fauntleroy Julian, to join UNIA and to perform aerial stunts to raise its profile. The group also launched its Booker T. Washington University from the UNIA-run Phyllis Wheatley Hotel on West 136th Street. He also finally succeeded in securing a UNIA delegation to the League of Nations, sending five members to represent the group to Geneva. Garvey also proposed marriage to his secretary, Jacques. She accepted, although later stated: "I did not marry for love. I did not love Garvey. I married him because I thought it was the right thing to do." They married in Baltimore in July 1922. She proposed that a book of his speeches be published; it appeared as The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, although the speeches were edited to remove more inflammatory material. That year, UNIA also launched a new newspaper, the Daily Negro Times.

At UNIA's August 1922 convention, Garvey called for the impeachment of several senior UNIA figures, including Adrian Johnson and J. D. Gibson, and declared that the UNIA cabinet should not be elected by the organisation's members, but appointed directly by him. When they refused to step down, he resigned both as head of UNIA and as Provisional President of Africa, probably in an act designed to compel their own resignations. He then began openly criticising another senior member, Reverend James Eason, and succeeded in getting him expelled from UNIA. With Eason gone, Garvey asked the rest of the cabinet to resign; they did so, at which he resumed his role as head of the organisation. In September, Eason launched a rival group to UNIA, the Universal Negro Alliance. In January 1923, Eason was assassinated by Garveyites while in New Orleans. Hoover suspected that the killing had been ordered by senior UNIA members, although Garvey publicly denied any involvement; he nevertheless launched a defense fund campaign for Eason's killers.

Following the murder, eight prominent African-Americans signed a public letter calling Garvey "an unscrupulous demagogue who has ceaselessly and assiduously sought to spread among Negroes distrust and hatred of all white people". They urged the Attorney-General to bring forth the criminal case against Garvey and disband UNIA. Garvey was furious, publicly accusing them of "the greatest bit of treachery and wickedness that any group of Negroes could be capable of." In a pamphlet attacking them he focused on their racial heritage, lambasting the eight for the reason that "nearly all [are] Octoroons and Quadroons". DuBois—who was not among the eight—then wrote an article critical of Garvey's activities in the U.S. Garvey responded by calling DuBois "a Hater of Dark People", an "unfortunate mulatto who bewails every drop of Negro blood in his veins".

Trial: 1923

Having been postponed at least three times, in May 1923, the trial finally came to court, with Garvey and three other defendants accused of mail fraud. The judge overseeing the proceedings was Julian Mack, although Garvey disliked his selection on the grounds that he thought Mack an NAACP sympathiser. At the start of the trial, Garvey's attorney, Cornelius McDougald, urged him to plead guilty to secure a minimum sentence, but Garvey refused, dismissing McDougald and deciding to represent himself in court. The trial proceeded for over a month. Throughout, Garvey struggled due to his lack of legal training. In his three-hour closing address he presented himself as a selfless leader who was beset by incompetent and thieving staff who caused all the problems for UNIA and the Black Star Line. On 18 June, the jurors retired to deliberate on the verdict, returning after ten hours. They found Garvey himself guilty, but his three co-defendants not guilty.

Garvey was furious with the verdict, shouting abuse in the courtroom and calling both the judge and district attorney "damned dirty Jews". Imprisoned in the The Tombs jail while awaiting sentencing, he continued to blame a Jewish cabal for the verdict; in contrast, prior to this he had never expressed anti-semitic sentiment and was supportive of Zionism. When it came to sentencing, Mack sentenced Garvey to five years' imprisonment and a $1000 fine. The severity of the sentence—which was harsher than those given to similar crimes at the time—may have been a response to Garvey's anti-Semitic outburst. He felt that they had been biased because of their political objections to his meeting with the acting imperial wizard of the Ku Klux Klan the year before. In 1928, Garvey told a journalist: "When they wanted to get me they had a Jewish judge try me, and a Jewish prosecutor. I would have been freed but two Jews on the jury held out against me ten hours and succeeded in convicting me, whereupon the Jewish judge gave me the maximum penalty."

A week after the sentence, 2000 Garveyite protesters met at Liberty Hall to denounce Garvey's conviction as a miscarriage of justice. However, with Garvey imprisoned, UNIA's membership began to decline, and there was a growing schism between its Caribbean and African-American members. From jail, Garvey continued to write letters and articles lashing out at those he blamed for the conviction, focusing much of his criticism on the NAACP.

Out on bail: 1923–

In September, Judge Martin Manton awarded Garvey bail for $15,000—which was duly raised by UNIA—while he appealed his conviction. Again a free man, he toured the U.S., giving a lecture at the Tuskegee Institute. In speeches given during this tour he further emphasised the need for racial segregation through migration to Africa, calling the United States "a white man's country". He continued to defend his meeting with the KKK, describing them as having more "honesty of purpose towards the Negro" than the NAACP. Although he previously avoided involvement with party politics, for the first time he encouraged UNIA to propose candidates in elections, often setting them against NAACP-backed candidates in areas with high black populations.

—DuBois, in Crisis, May 1924.

In February 1924, UNIA put forward its plans to bring 3000 African-American migrants to Liberia. The latter's President, Charles D. B. King, assured them that he would grant them area for three colonies. In June, a team of UNIA technicians was sent to start work in preparing for these colonies. When they arrived in Liberia, they were arrested and immediately deported. At the same time, Liberia's government issued a press release declaring that it would refuse permission for any Americans to settle in their country. Garvey blamed DuBois for this apparent change in the Liberian government's attitude, for the latter had spent time in the country and had links with its ruling elite; DuBois denied the accusation. Later examination suggested that, despite King's assurances to the UNIA team, the Liberian government had never seriously intended to allow African-American colonisation, aware that it would harm relations with the British and French colonies on their borders, who feared the political radicalism it could bring with it.

After numerous attempts at appeal over 18 months were unsuccessful, he was taken into custody and began serving his sentence at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary on 8 February 1925. Two days later, he penned his well-known "First Message to the Negroes of the World From Atlanta Prison", wherein he made his famous proclamation: "Look for me in the whirlwind or the storm, look for me all around you, for, with God's grace, I shall come and bring with me countless millions of black slaves who have died in America and the West Indies and the millions in Africa to aid you in the fight for Liberty, Freedom and Life."

Professor Judith Stein has stated, "his politics were on trial." Garvey's sentence was eventually commuted by President Calvin Coolidge. Upon his release in November 1927, Garvey was deported via New Orleans to Jamaica, where a large crowd met him at Orrett's Wharf in Kingston. Though the popularity of the UNIA diminished greatly following Garvey's expulsion, he nevertheless remained committed to his political ideals.

Later years

In 1928, Garvey travelled to Geneva to present the Petition of the Negro Race. This petition outlined the worldwide abuse of Africans to the League of Nations. In September 1929, he founded the People's Political Party (PPP), Jamaica's first modern political party, which focused on workers' rights, education, and aid to the poor. Also in 1929, Garvey was elected councillor for the Allman Town Division of the Kingston and St. Andrew Corporation (KSAC). In July 1929, the Jamaican property of the UNIA was seized on the orders of the Chief Justice. Garvey and his solicitor attempted to persuade people not to bid for the confiscated goods, claiming the sale was illegal and Garvey made a political speech in which he referred to corrupt judges. As a result, he was cited for contempt of court and again appeared before the Chief Justice. He received a prison sentence, as a consequence of which he lost his seat. However, in 1930, Garvey was re-elected, unopposed, along with two other PPP candidates.

In April 1931, Garvey launched the Edelweiss Amusement Company. He set the company up to help artists earn their livelihood from their craft. Several Jamaican entertainers—Kidd Harold, Ernest Cupidon, Bim & Bam, and Ranny Williams—went on to become popular after receiving initial exposure that the company gave them. In 1935, Garvey left Jamaica for London. He lived and worked in London until his death in 1940. During these last five years, Garvey remained active and in touch with events in war-torn Ethiopia (then known as Abyssinia) and in the West Indies. In 1937, he wrote the poem Ras Nasibu Of Ogaden in honor of Ethiopian Army Commander (Ras) Nasibu Emmanual. In 1938, he gave evidence before the West India Royal Commission on conditions there. Also in 1938 he set up the School of African Philosophy in Toronto to train UNIA leaders. He continued to work on the magazine The Black Man.

While imprisoned Garvey had corresponded with segregationist Earnest Sevier Cox who was lobbying for legislation to "repatriate" African Americans to Africa. Garvey's philosophy of black racial self-reliance could be combined with Cox's White Nationalism – at least in sharing the common goal of an African Homeland. Cox dedicated his short pamphlet "Let My People Go" to Garvey, and Garvey in return advertised Cox' book "White America" in UNIA publications.

In the summer of 1936, Garvey travelled from London to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, for five days of speeches and appearances.The Universal Negro Improvement Association had purchased a hall on College Street in that city and a convention was held, where Garvey was the principal speaker. His five-day visit was front-page news.

In 1937, a group of Garvey's rivals called the Peace Movement of Ethiopia openly collaborated with the United States Senator from Mississippi, Theodore Bilbo, and Earnest Sevier Cox in the promotion of a repatriation scheme introduced in the US Congress as the Greater Liberia Act. Bilbo, an outspoken supporter of segregation and white supremacy who was attracted by the ideas of black separatists like Garvey, proposed an amendment to the federal work-relief bill on 6 June 1938, proposing to deport 12 million black Americans to Liberia at federal expense to relieve unemployment. He took the time to write a book entitled Take Your Choice, Separation or Mongrelization, advocating the idea. Garvey praised him in return, saying that Bilbo had "done wonderfully well for the Negro". During this period, Evangeline Rondon Paterson, the future grandmother of the 55th Governor of New York State, David Paterson, served as his secretary.

Death and burial

While living in London, Garvey suffered a stroke which left him largely paralysed. His rival, George Padmore, spread rumours of Garvey's death while the latter was still alive; this led to many newspapers publishing premature obituaries, many of which he read. Garvey then suffered a second stroke and died on 10 June 1940. His body was interred in a vault in the catacombs of St Mary's Roman Catholic Church in Kensal Green Cemetery, West London.

Various wakes and memorials were held for Garvey, especially in New York City and Kingston. In Harlem, a procession of mourners paraded to his memorial service. Some Garveyites refused to believe Garvey had died, even when confronted with photographs of his body in its coffin, insisting that this was part of a conspiracy to undermine his movement. Both Ashwood and Jacques presented themselves as the "widow of Marcus Garvey" and Ashwood launched legal action against Jacques in an attempt to secure control over his body.

In 1964, his body was removed from the crypt and taken to Jamaica, where the government named him Jamaica's first National Hero and reinterred his body at a shrine in National Heroes Park, Kingston. The monument, designed by G. C. Hodges, consists of a tomb at the center of a raised platform in the shape of a black star, a symbol often used by Garvey. Behind it, a peaked and angled wall houses a bust, by Alvin T. Marriot,of Garvey, which was added to the park in 1956 (before his reinterment) and relocated after the construction of the monument.

Ideology

Ideologically, Garvey was a black nationalist. His ideas were influenced by a range of sources. According to Grant, while in London Garvey displayed "an amazing capacity to absorb political tracts, theories of social engineering, African history and Western Enlightenment." Garvey was exposed to the ideas about race that were prevalent at the time; his ideas on race were also heavily informed by Blyden's writings. While in the U.S., ideas about the need for black racial purity became central to his thought.

During the late 1910s and 1920s, Garvey was also influenced by the ideas of the Irish independence movement, to which he was sympathetic. He saw strong parallels between the British subjugation of Ireland and the broader subjugation of black people, and identified strongly with the Irish independence leader Éamon de Valera. He wrote a letter to Valera stating that "We believe Ireland should be free even as Africa shall be free for the Negroes of the world". For Garvey, Ireland's Sinn Féin and the Irish independence movement served as a blueprint for his own black nationalist cause. He also admired the Indian independence movement then seeking freedom from the British Empire, describing Mahatma Gandhi as "one of the noblest characters of the day".

His essential ideas about Africa are stated in an editorial in the Negro World entitled "African Fundamentalism", where he wrote: "Our union must know no clime, boundary, or nationality ... to let us hold together under all climes and in every country ..."

Tony Martin stated that when Garvey returned to Jamaica and established UNIA, he displayed "a burning desire to rescue his people from ignorance and poverty". Cronan believed that Garvey exhibited "antipathy and distrust for any but the darkest-skinned Negroes". Garvey accused Du Bois and NAACP of promoting "amalgamation or general miscegenation". Garvey was willing to collaborate with white supremacists in the U.S. to achieve his aims. They were willing to work with him because his approach effectively acknowledged the idea that the U.S. should be a country exclusively for white people and would abandon campaigns for advanced rights for African-Americans within the U.S.

Pan-Africanism

In the wake of the First World War, Garvey called for the formation of "a United Africa for the Africans of the World". Garvey never visited Africa himself. Garvey did not believe that all African-Americans should migrate to Africa, but that instead only an elite selection, namely those of the purest African blood, should do so. The rest of the African-American population, he believed, should remain in the United States, where they would be extinct within fifty years. He promoted ideas of racial separatism, but did not stress the idea of racial superiority.

— Garvey, August 1920

Garvey's critics thought that his views of Africa were romanticised and ignorant. The Jamaican writer and poet Claude McKay for instance noted that Garvey "talks of Africa as if it were a little island in the Caribbean Sea. The scholar of African-American studies Wilson S. Moses stated that rather than respecting indigenous African cultures, Garvey's views of an ideal united Africa were based on "the imperial model of Victorian England". When extolling the glories of Africa, he cited the ancient Egyptians and Ethiopians who had built empires and large-scale buildings, which he saw as evidence of civilisation, rather than the smaller-scale societies of other parts of the continent. Moses thought that Garvey "had more affinity for the pomp and tinsel of European imperialism than he did for black African tribal life".

Garvey's envisioned Africa was to be a one-party state in which the president could have "absolute authority" to appoint "all his lieutenants from cabinet ministers, governors of States and Territories, administrators and judges to minor offices". According to Moses, the future African state which Garvey envisioned was "authoritarian, elitist, collectivist, racist, and capitalistic", suggesting that it would have resembled the Haitian government of François Duvalier. Garvey told the historian J. A. Rogers that he and his followers were "the first fascists", adding that "Mussolini copied Fascism from me, but the Negro reactionaries sabotaged it". He argued that mixed-race people would be bred out of existence; this hostility to black people not deemed of "pure" African blood was an idea that Garvey shared with Blyden.

A proponent of the Back-to-Africa movement, Garvey called for a vanguard of educated and skilled African-Americans to travel to West Africa, a journey facilitated by his Black Star Line. Garvey stated that "The majority of us may remain here, but we must send our scientists, our mechanics and our artisans and let them build railroads, let them build the great educational and other institutions necessary", after which other members of the African diaspora could join them. He was aware that the majority of African-Americans would not want to move to Africa until it had the more modern comforts that they had become accustomed to in the U.S.

Economic views

Economically, he supported capitalism, stating that "capitalism is necessary to the progress of the world, and those who unreasonably and wantonly oppose or fight against it are enemies to human advancement." He proposed that no individual should be allowed to control more than one million dollars and no company more than five million.

In Garvey's opinion, "without commerce and industry, a people perish economically. The Negro is perishing because he has no economic system". In the U.S., he promoted a capitalistic ethos for the economic development of the African-American community. He wanted to achieve greater financial independence for the African-American community, believing that it would ensure greater protection from discrimination. He admired Booker T. Washington's economic endeavours although was critical of his individualistic focus: Garvey believed African-American interests would best be advanced if businesses included collective decision making and group profit sharing. While in Harlem, he envisioned the formation of a global network of black people trading amongst themselves, believing that his Black Star Line would contribute to this aim. His emphasis on capitalist ventures meant, according to Grant, that Garvey "was making a straight pitch to the petit-bourgeois capitalist instinct of the majority of black folk."

There is no evidence that Garvey was ever sympathetic to socialism. He viewed the communist movement as a white person's creation that was not in the interests of African-Americans. He stated that communism was "a dangerous theory of economic or political reformation because it seeks to put government in the hands of an ignorant white mass who have not been able to destroy their natural prejudices towards Negroes and other non-white people. While it may be a good thing for them, it will be a bad thing for the Negroes who will fall under the government of the most ignorant, prejudiced class of the white race." He urged African-Americans not to support the Communist Party.

Black Christianity

— Garvey, on viewing God as black, 1923

Grant noted that "Garveyism would always remain a secular movement with a strong under-tow of religion".

Garvey sought to create a black religion, with Cronon suggesting that Garvey promoted "racist ideas about religion". Garvey emphasised the idea of black people worshipping a God who was also depicted as black. In doing so, he did not make use of pre-existing forms of black-dominant religion. Garvey had little experience with these, having attended a white-run Wesleyan congregation as a child and later converting to Roman Catholicism. Reflecting his own Catholicism, he wanted this black-centric Christianity to be as close to Roman Catholicism as possible.

Personality and personal life

Physically, Garvey was short and stocky. He suffered from asthma, and was prone to lung infections; throughout his adult life he was affected by bouts of pneumonia.Tony Martin called Garvey a "restless young man", while Grant thought that in his early years Garvey had a "naïve but determined personality". Grant noted that Garvey "possessed a single-mindedness of purpose that left no room for the kind of spectacular failure that was always a possibility".

He was eloquent and a good orator, with Cronon suggesting that his "peculiar gift of oratory" stemmed from "a combination of bombast and stirring heroics". Grant described Garvey's public speeches as "strange and eclectic - part evangelical […] partly formal King's English, and part lilting Caribbean speechifying". Garvey enjoyed arguing with people, and wanted to be seen as a learned man; he read widely, particularly in history. Cronon suggested that "Garvey's florid style of writing and speaking, his fondness for appearing in a richly colored cap and gown, and his use of the initials "D.C.L." after his name were but crude attempts to compensate" for his lack of formal academic qualifications. Grant thought Garvey was an "extraordinary salesman who'd developed a philosophy where punters weren't just buying into a business but were placing a down payment on future black redemption." Even his enemies acknowledged that he was a skilled organiser and promoter.

For Grant, Garvey was "a man of grand, purposeful gestures". He thought that the black nationalist leader was an "ascetic" who had "conservative tastes". Garvey was a teetotaller who regarded alcohol consumption as morally reprehensible. He enjoyed dressing up in military costumes.Grant noted that Garvey had a "tendency to overstate his achievements". In 1947, the Jamaican historian J. A. Rogers included Garvey in his book, the World's Great Men of Colour, where he noted that "had [Garvey] ever come to power, he would have been another Robespierre", resorting to violence and terror to enforce his ideas.

In 1919, he married Amy Ashwood in a Roman Catholic ceremony, although they separated after three months. The New York court would not grant Garvey a divorce, but he later obtained ne in Jackson County, Missouri. Ashwood contested the legitimacy of this divorce and for the rest of her life maintained that she was Garvey's legitimate spouse. Garvey collected antique ceramics and enjoyed going around antique shops and flea markets searching for items to add to his collection.

Reception and legacy

— Edmund David Cronon 1955

Garvey was a polarizing figure. Grant noted that he was "revered and reviled in equal measure", and that views on him divided largely between two camps, "one that wants to skewer him as a charlatan and the other that seeks to elevate him to the status of a saint". Cronon noted that different perspectives on him had been offered, and that he was varyingly views as "strident demagogue or dedicated prophet, martyred visionary or fabulous con man?"

While living in the U.S., he was often referred to—sometimes sarcastically—as the "Negro Moses", implying that like the Old Testament figure, he would lead his people out of their situation. Grant described Garvey as "Jamaica's first national hero". Martin noted that by the time Garvey returned to Jamaica in the 1920s, he was "just about the best known Black man in the whole world." His ideas influenced many black people who never became paying members of UNIA. He noted that in the years following Garvey's death, his life was primarily presented by his political opponents. Critics like Du Bois often mocked him for his outfits and the grandiose titles he gave to himself; in their view, he was embarrassingly pretentious. According to Grant, much of the established African-American middle-class were "perplexed and embarrassed" by Garvey, who thought that the African-American working classes should turn to their leadership rather than his. Concerns were also raised that his violent language was inflaming many Garveyites to carry out violent acts against his critics.

In 1955, Cronon described Garvey as someone who "awakened fires of Negro nationalism that have yet to be extinguished". Cronon added that while Garvey "achieved little in the way of permanent improvement for his people, […] he did help to point out the fires that smolder in the Negro world." For Cronon, "Garvey's work was important largely because more than any other single leader he helped to give Negroes everywhere a reborn feeling of collective pride and a new awareness of individual worth." Grant thought that Garvey, along with Du Bois, deserved to be seen as the "father of Pan-Africanism".

Garvey has received praise from those who see him as a "race patriot". Many African-Americans see Garvey as having encouraged a sense of self-respect among black people. In 2008, the American writer Ta-Nehisi Coates described Garvey as the "patron saint" of the black nationalist movement. Writing for The Black Scholar in 1972, the scholar of African-American studies Wilson S. Moses expressed concern about "that uncritical adulation of him that leads to the practice of red baiting and to the divisive rhetoric of "Blacker-than-thou"" within African-American political circles. He argued that Garvey was wrongly seen as a "man of the people" because he had been born to a petty bourgeoise background and had "enjoyed cultural, economic, and educational advantages few of his black contemporaries were priviledged [sic] as to know."

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Garvey on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Influence

In Jamaica, Garvey was largely forgotten in the years after his death, but interest in him was revived by the Rastafari religious movement. Jacques wrote a book about her late husband, Garvey and Garveyism, and after finding that no publishers were interested in it she self-published the volume in 1963. In 1975 the reggae artist Burning Spear released the album Marcus Garvey.

Interest in Garvey's ideas would also be revived in the 1960s through the growth of independent states across Africa and the emergence of the Black Power movement in the United States. In his autobiography, Kwame Nkrumah, the prominent Pan-Africanist activist who became Ghana's first post-independence president, acknowledged having been influenced by Garvey. The flag that Ghana adopted when it became independent adopted the colours of UNIA. In November 1964, Garvey's body was removed from West Kensal Green Cemetery and taken to Jamaica. There, it lay in state in Kingston's Roman Catholic Cathedral before a motorcade took it to King George VI Memorial Park, where it was again buried.

During a trip to Jamaica, Martin Luther King and his wife Coretta Scott King visited Garvey's shrine on 20 June 1965 and laid a wreath. In a speech he told the audience that Garvey "was the first man of color to lead and develop a mass movement. He was the first man on a mass scale and level to give millions of Negroes a sense of dignity and destiny. And make the Negro feel he was somebody." Vietnamese Communist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh said Garvey and Korean nationalists shaped his political outlook during his stay in America.

In the 1980s, Garvey's two sons launched a campaign requesting that the U.S. government issue a pardon for their father. In this they had the support of Harlem Congressman Charles Rangel. In 2006, Jamaican Prime Minister Portia Simpson-Miller tasked various Jamaican lawyers with investigating how they could assist this campaign. The Obama Administration declined to pardon Garvey in 2011, writing that its policy is not to consider requests for posthumous pardons.

There have been several proposals to make a biopic of Garvey's life. Those mentioned in connection with the role of Garvey have included the Jamaican-born actor Kevin Navayne and the British-born actor of Jamaican descent Delroy Lindo.

Garvey as religious symbol

Rastafari

According to the scholar of religion Maboula Soumahoro, the Abrahamic religion of Rastafari "emerged from the socio-political ferment inaugurated by Marcus Garvey", while for the sociologist Ernest Cashmore, Garvey was the "most important" precursor of the Rastafari movement. Rastafari does not promote all of the views that Garvey espoused, but nevertheless shares many of the same perspectives, with many Rastas regarding Garvey as a prophet. Some Rastas also organise meetings, known as Nyabinghi Issemblies, to mark Garvey's birthday.

His beliefs deeply influenced the Rastafari, who took his statements as a prophecy of the crowning of Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia. Early Rastas were associated with his Back-to-Africa movement in Jamaica. This early Rastafari movement was also influenced by a separate, proto-Rasta movement known as the Afro-Athlican Church that was outlined in a religious text known as the Holy Piby—where Garvey was proclaimed to be a prophet as well. Garvey himself never identified with the Rastafari movement.

Memorials

Garvey is remembered through a number of memorials worldwide. Most of them are in Jamaica, England and the United States; others are in Canada and several nations in Africa.

Jamaica

Garvey's birthplace, 32 Market Street, St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica, has a marker signifying it as a site of importance in the nation's history. His likeness was on the 20-dollar coin and 25-cent coin of the Jamaican dollar.

Marcus Garvey Day

In 2012 the Jamaican government declared August 17 as Marcus Garvey Day. The Governor General's proclamation stated "from here on every year this time, all of us here in Jamaica will be called to mind to remember this outstanding National Hero and what he has done for us as a people, and our children will call this to mind also on this day" and went on to say "to proclaim and make known that the 17th Day of August in each year shall be designated as Marcus Garvey Day and shall so be observed."

United States

The Brownsville neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York City, is home to Marcus Garvey Village, whose construction was completed in 1976. This building complex is home to the first energy storage microgrid at an affordable housing property in the country. It will use the energy storage system to cut electricity costs, improve grid reliability, and provide backup power during extended outages.