Quick Facts

Biography

Henry Augustus Peirce (December 15, 1808 –July 29, 1885) was an American businessman and diplomat. Some sources spell his last name as Pierce.

Early life and business

He was born in Dorchester Massachusetts (now part of Boston) December 15, 1808. His father was Joseph Hardy Peirce (1773–1832) son of Joseph Peirce (1748–1812) and his mother was Frances Temple. He had at least one brother and five sisters. He attended public schools in Boston, and then about 1822 worked for his father and uncle as a court clerk. On October 24, 1824 he enrolled on the crew of the merchant ship Griffon mastered by his brother Marus T. Peirce. On March 25, 1825 the Griffon landed in Honolulu for provisions. He was promoted to ship's clerk for the three-year trading voyage on the west coast of British Columbia. In September 1828 the Griffon was back in Honolulu, and Peirce stayed while his brother returned.

Peirce worked as a clerk for fellow ex-New Englander James Hunnewell (1794–1869), who ran a mercantile business. He eventually became a partner, and then owner when Hunnewell left in 1830. In 1834 he chartered the Becket from King Kamehameha III and traveled to China trading sandalwood and merchandise to the Kamchatka Peninsula. In 1835 he formed a partnership with one of the commanders of his ships, Captain Charles Brewer (1804–1885), and continued to develop the shipping business. Some time around 1828 he took a common-law wife (before marriages were legally required to be recorded) named Kahoa, or Virginia Rives, whose mother was a Hawaiian noble and father was Jean-Baptiste Rives, the French former Secretary of Kamehameha II. They had a son named Henry E. Pierce in 1830 (changing the spelling the last name), whom he took to the mainland for his education. Kahoa divorced in 1837, and Henry E. and his mother moved to Kamchatka.

In 1836 after sailing on one of his ships to China, he traveled to New York. It was his first time back in his native country for 12 years. On January 19, 1837 he sailed again out of Boston to Brazil. He then went around Cape Horn to Peru, where he was employed as Peruvian Consul to Hawaii. In November 1837 he sold a ship in Valparaíso, Chile and traveled overland back to Brazil. From there he sailed back to New York and Boston. He married Susan R. Thompson on July 3, 1838. Less than a year later he purchased the schooner Morse and left again on April 21, 1839. Via Cape Horn again, he arrived in Honolulu October, 1839. In November 1841 he sailed for Alta California. Although there were plans for American settlement, it was still a spare Spanish outpost. In a letter to Thomas Cummins in February 1841 he wrote:

"In my opinion California will become, in its future history, a second Texas....in less than six years more than fifteen thousand persons will have emigrated to California...we shall, I hope, see the country governed by our own enlightened laws, and the people speaking our own language."

He sailed south down the California coast, continuing to trade as he went. After reaching San Blas, Mexico he traveled by land to Mexico City and the eastern coast, then boat to Cuba. From there he traveled north to Washington, D.C. where he met with Daniel Webster who was then Secretary of State. Finally he saw his family again for the first time in three years.

In 1843 Peirce retired from the Honolulu business, which became C. Brewer & Co. After some other owners, the name would be changed back by Brewer's nephew, the name it would keep through the 21st century. It became one of the Big Five companies that dominated the economy of the Territory of Hawaii.

In 1844 Peirce took a tour of Europe, but continued to invest in shipping ventures. One of his ships was chartered in 1847 to send provisions to Monterey, California for the U.S. forces there. At the start of the California Gold Rush, he sailed on the ship Montreal on January 19, 1849. When they arrived in San Francisco in July 1849, the entire crew left to join the gold rush. By September he had gathered another crew and sent the Montreal back to New England, while he went to Honolulu. He invested in a small sugarcane plantation at Līhuʻe on Kauaʻi island with Charles Reed Bishop and William Little Lee, but it failed due to uneven rainfall. After William Harrison Rice constructed an irrigation system, the plantation was reorganized in 1859.

Meanwhile, Peirce headed off to China. There he joined a venture sending Chinese goods to San Francisco at a great profit. Finally in April 1850 he returned to Boston after circumnavigating the earth. Seeing the new market potential, he joined his old friends Hunnewell and Brewer in a partnership sending goods between Hawaii and California. This time he stayed behind with his wife and two children, acting as Consul for Hawaii in New England.

The outbreak of the American Civil War and financial scandals caused great losses in the 1860s. He helped provide transportation for troops, and was meeting at Port Royal, South Carolina with Admiral William Reynolds whom he had known in Hawaii in 1840, when he heard Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated. He attended the funeral procession on his way home. In 1866 he invested in a venture to use freed slaves for a cotton plantation in Yazoo County, Mississippi, but that venture also failed. He had to sell his Beacon Street mansion to settle his debts.

Diplomacy

On May 10, 1869 Peirce was appointed U.S. Minister to Hawaiian Islands, and confirmed by the U.S. Senate on December 21, 1869. This time he traveled on the transcontinental railroad and arrived in Honolulu by June 15, 1869, twenty years after his last visit. On July 19, 1869 he presented his credentials at the court of King Kamehameha V. When this last ruler of the House of Kamehameha died on December 11, 1872 without naming a successor, the Kingdom faced a political crisis. The popular King Lunalilo then died on February 3, 1874, again with no successor, and the crisis deepened when King Kalākaua was elected by the legislature. Supporters of Queen Emma of Hawaii who was popular with the people, started to riot. At the request of C. R. Bishop who was Minister of the Interior, Peirce called out American troops from the sloops USS Tuscarora and USS Portsmouth.

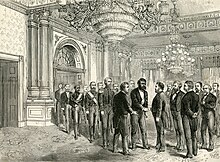

On November 17, 1874 Kalākaua left accompanied by Peirce and some other government ministers on a visit to Washington, D.C. which was the first state visit of a ruling monarch to the United States. They were guests at a state dinner and reception with President Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Cabinet. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 allowed use of Pearl Harbor by the U.S. in exchange for elimination of tariffs on Hawaiian goods. This was a careful compromise between those who wanted full annexation of the islands or cessation of the Harbor, and others who opposed any threats to sovereignty. Peirce had worked for years on arranging the trip and treaty, interrupted by the deaths of the two previous monarchs. Kalākaua offered Peirce the Royal Order of Kamehameha, but he had to wait until no longer employed by the U.S. Government to accept.

He served until being replaced by James M. Comly on September 25, 1877. On November 17, 1877 he arrived in San Francisco, but the cold weather convinced him to return to Hawaii January 8, 1878. As he was about to leave, Kalākaua offered him the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Kingdom of Hawaii on March 1. There was a shortage of experienced politicians and diplomats willing to serve; in fact, the Minister from the Kingdom to the United States was fellow New Englander Elisha Hunt Allen. Americans were negotiating on both sides of the 1875 treaty. Allen also was chief justice of the Hawaii Supreme Court.

However, after a no confidence vote was narrowly defeated by the legislature, Kalākaua replaced his entire cabinet on July 3, 1878. Peirce served for one session in the House of Nobles, and was sent to an exhibition in Boston in 1883. He returned to Boston one more time and then resided in San Francisco where he died on July 29, 1885.