Quick Facts

Biography

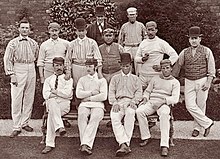

George Ulyett (21 October 1851, Sheffield – 18 June 1898, Sheffield) was an English all-round cricketer, noted particularly for his very-aggressive batsmanship. A well-liked man (who, in later years, kept a pub in his native Sheffield), Ulyett was popularly known as "Happy Jack", once musing memorably that Yorkshire played him only for his good behaviour and his whistling. A fine all round sportsman, Ulyett played football in the 1882–83 and 1883–84 seasons as goalkeeper for Sheffield Wednesday.

Cricket career

Born in Pitsmoor, Sheffield, Ulyett joined the local Pitsmoor club at the age of sixteen and, from 1871 to 1873, played as a professional in Bradford. In 1873, he made his Yorkshire debut, at Bramall Lane against Sussex, and remained a valued member of the team for the next twenty years, passing 1,000 runs in ten seasons and fifty wickets in three. In his best batting year of 1883 Ulyett achieved the remarkable feat of scoring 1,562 runs – eleven runs from being the leading run scorer – without a single century. Not until Charles Harris in 1935 did any batsman score more runs without a century, and only David Green in 1965 – a somewhat similar style of hard hitting opener – has since come remotely so close to being the leading run scorer of a season without scoring a century. He took his career-best figures of seven for thirty against Surrey in 1878 and, in 1887, made his highest score, 199 not out against Derbyshire.

Ulyett was a member of James Lillywhite Junior's tour of Australia in 1876/77. After the visitors' early defeat at the hands of a XV of New South Wales, the local press pronounced them "by a long way the weakest side that have ever played in the colonies, notwithstanding the presence of Shaw, who is termed the premier bowler of England. If Ulyett, Emmett, and Hill are specimens of the best fast bowling in England, all we can say is, either they have not shown their proper form, or British bowling has sadly deteriorated." Not long after, however in an eleven-a-side first-class match against New South Wales, Ulyett scored an excellent 94 to guide Lillywhite's team to victory.

Ulyett also played in the first-ever Test match, staged at the MCG, during that tour. His first real action in Test cricket came when he held onto a catch off the bowling of James Southerton to dismiss Billy Midwinter for five. With the bat, however, Ulyett failed in the first innings, lasting just a quarter of an hour before Nat Thomson had him trapped in front; in the second innings, however, with England in dire straits, he fought hard with John Selby for about 45 minutes—but then the rampant Tom Kendall got one through his defences and effectively brought an end to England's resistance, the match being lost by 45 runs. In bowling, Ulyett took three for 39 in the second innings, his first wicket being that of Charles Bannerman, who famously managed an incredible 165 out of Australia's first innings total of 245 (or 67.3 per cent of it, still a Test-Match record). This amazing effort finally came to an end when the toiling Ulyett let loose a sharp, rising bouncer that found its way through Bannerman's primitive gloving and struck him a blow on the index finger, splitting it open rather badly. A short delay revealed the fact that Bannerman could no longer grip his bat properly and that, therefore, he would have to retire. The Australian opener walked off, wincing from the pain in his bloodied right hand. George Ulyett, although never regarded as a truly-quick bowler, could nevertheless do real damage on occasion. Bannerman was unable to field, and, in the second innings, when Ulyett dismissed him again (this time in orthodox fashion—bowled), he faced just nine deliveries.

In the second game, also at Melbourne, Ulyett showed his worth as a batsman, making 52 and 63 to secure an England win by four wickets. On Day 2 (02-Apr-1877) George joined A Greenwood when England were 72 for 4. George partnered Greenwood and Tom Emmett. His 52 was part of a career total of 86, 2nd highest by a Test Player at that time. Thereafter, he was a regular pick for the England Test side, with his batting and bowling backed up by some fine displays of fielding.

Ulyett played 25 Tests in total—it was by far the longest career of any England cricketer to play in that inaugural Test—and several times changed the course of a match. At Lord's in 1884, in the second innings, he returned an analysis of 39.1–23–36–7 (four-ball overs) to reduce the Australians from 60/1 to 145 all out and force a remarkable innings victory.

Included in that haul was one of the most famous caughts-and-bowled ever taken. Ulyett sent down a straight half-volley to Bonnor, who drove at it with all his considerable might and got it right out of the middle of the bat. The ball flew back towards the bowler with a resounding crack. It seemed to Ulyett barely to have left his hand—yet already it was flying back to him at what seemed like the speed of light. He had no time to judge it but held out the right hand instinctively, and the leather stuck, right in the middle of his palm. With the sound of Bonnor's stroke still echoing about the ground, many eyes in the gallery were looking for the area near the boundary where they thought that the ball would land. The eyes of George Giffen, the non-striker, were among the wanderers, and he was certain that everyone else must be looking for it, too: indeed, a segment of the crowd, in panic, had even opened up a space in the ring in anticipation of the ball’s descent. Giffen reckoned it to have been a very mighty drive indeed—but he could not see where it had gone. When, finally, his and other eyes were diverted back towards the pitch, they noticed Ulyett celebrating and Bonnor was departing. It soon dawned on them that Ulyett had taken the catch. Although Ulyett felt no pain in the centre of his hand, there was definitely a fair amount of it on the outside. Bonnor looked at him disgustedly, thinking it almost immoral to have done such a thing, and he walked off gloomily. The England players gathered around Ulyett in wonderment. They seemed to the Wisden correspondent to be curious as to what kind of man this was—although they were also keen to congratulate him on his evasion of impending danger. The looks on the faces of Allan Steel and Alfred Lyttelton would stay with Wisden's man for a long time. WG Grace and Lord Harris both told Ulyett that he was foolish to have attempted to take the catch: had it hit his wrist or arm instead, that bone would surely have snapped. Giffen believed that this was one of the finest catches that he had ever seen, and, although on the team which it had adversely affected, he definitely appreciated it.

Earlier, in 1881/82, Ulyett had made his only Test century, hitting 149 at Melbourne in a drawn match.

The end of Ulyett's international career came in somewhat controversial fashion. At Lord's in 1890 he had made 74 out of 173 to shore up England's first innings after they had slumped to 20/4, putting on 72 with Maurice Read. However, he did not appear at The Oval three weeks later because the authorities at Yorkshire refused to release him from county duty, requiring him instead to play against Middlesex at Bradford. (He made 11 and did not bowl a ball.)

He played on for Yorkshire for a few more years, but bowled increasingly little and did not take a wicket after 1891. The last of his 18 hundreds came against Middlesex in 1892, and he bade a quiet farewell from the first-class game in scoring just nine at Bramall Lane in August 1893.

Death

After retirement, his health began to fail and five years later he died in Pitsmoor, aged just 46, of pneumonia contracted while attending a Yorkshire match at Sheffield. His popularity was shown by the turnout of 4,000 for his funeral.

"Of large build, ruddy countenance and of cheery disposition, Ulyett was a typical Yorkshireman" He was clean hitter of a cricket ball and a fast bowler with "a high action". Lyttleton also says he was not a particularly skilful bowler: "He pounded away straight and hard but I never thought that he used his head much".

Libra

Libra